Simon Oakland

back| Full Name | Isidor Simon Weiss |

| Stage Name | Simon Oakland |

| Born | August 28, 1915 |

| Birthplace | Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | August 29, 1983, (aged 68), Cathedral City, California, U.S. |

| Buried | Unknown |

| Married to | Lois Lorraine Porta |

| Children | One daughter, Barbara |

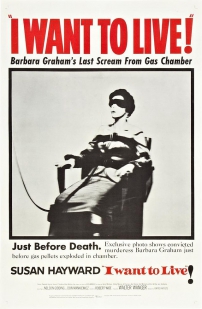

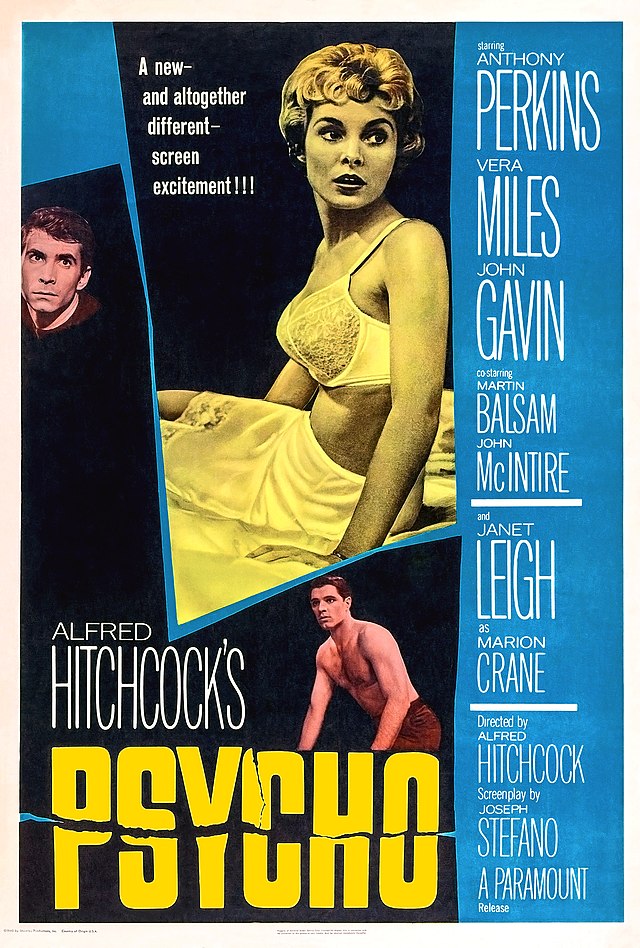

| Notable films | I Want to Live! (1958) - Psycho (1960) - West Side Story (1961) - Bullit (1968) |

Simon Oakland

Biography and Movie Career

Simon Oakland (born Isidor Simon Weiss, 1915–1983) was a commanding American character actor known for his deep voice, intense presence, and roles as tough authority figures. Originally a concert violinist, he transitioned to acting in the 1940s, earning acclaim on Broadway before moving to film and television.

He gained lasting recognition as the psychiatrist in Psycho (1960) and Lt. Schrank in West Side Story (1961). Oakland appeared in over 130 screen productions, including Bullitt, The Sand Pebbles, and cult TV series Kolchak: The Night Stalker. Despite never winning major awards, he was widely respected for his consistency and gravitas.

Married to Lois Lorraine Porta, he had one daughter, Barbara. Oakland died of colon cancer in 1983, a day after his 68th birthday, leaving behind a legacy as one of Hollywood’s most compelling and underrated character actors.

Related

Simon Oakland (1915 – 1983)

The Voice of Authority in the Shadows of Hollywood

Simon Oakland, born Isidor Simon Weiss on August 28, 1915, in Brooklyn, New York, emerged as one of Hollywood's most memorable character actors—a man with a commanding presence, deep voice, and the rare ability to dominate a scene, even in supporting roles. Though best remembered for portraying tough authority figures, Oakland's life and career were shaped by a much broader palette of experience, talent, and passion.

Early Life and Musical Roots

Simon was born to Jewish immigrants—his father from Romania and his mother from Russia—who settled in the vibrant, working-class neighborhoods of Brooklyn. Raised during the difficult years of World War I and the Great Depression, Simon developed a keen sense of discipline and a deep appreciation for the arts at a young age.

His first artistic love wasn’t acting—it was music. A gifted violinist, Simon trained seriously throughout his youth, eventually performing professionally in symphony orchestras and as a soloist. Music remained a lifelong passion and was reportedly a refuge from the often harsh and competitive world of acting.

From Violinist to Actor

By the 1940s, Oakland began exploring acting, drawn to the emotional range and storytelling power of the stage. He adopted the stage name "Simon Oakland" (Oakland being his mother's maiden name) and studied the craft intensively. His rich voice and sharp intelligence made him a natural onstage. He broke into theater with roles on Broadway, appearing in plays like Light Up the Sky, Inherit the Wind, and The Shrike, earning critical acclaim for his forceful, complex performances.

As television and film began to overtake the stage in popularity, Oakland transitioned to the screen. His first uncredited film role was in The Desperate Hours (1955), but it was his performance in I Want to Live! (1958)—playing a relentless newspaper reporter—that launched his screen career in earnest. His performance captured the attention of directors and casting agents, leading to a series of high-profile roles.

Career Highlights and Acting Persona

Simon Oakland quickly became a fixture in film and television throughout the 1960s and 1970s. He had a particular knack for portraying men in positions of authority—detectives, psychiatrists, generals—roles that suited his stern demeanor and resonant voice. Yet he always managed to imbue these characters with subtle humanity, never allowing them to become caricatures.

His most iconic role came in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), where he played Dr. Fred Richman, the psychiatrist who delivers the film’s final, chilling explanation of Norman Bates’ psychosis. That performance remains one of the most analyzed monologues in film history.

Other major films included:

- Lt. Schrank in West Side Story (1961), the hard-nosed police detective trying to contain the gang violence of New York’s streets.

- Captain Sam Bennett in Bullitt (1968), opposite Steve McQueen.

- Supporting roles in The Sand Pebbles (1966), On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (1970), The Hunting Party (1971), Chato’s Land (1972), and Emperor of the North (1973).

In addition to film, Oakland was prolific on television, appearing in more than 130 series and TV movies. He made guest appearances on Perry Mason, The Outer Limits, The Twilight Zone, The Rockford Files, and Hawaii Five-O. One of his most beloved TV roles was as Tony Vincenzo, the skeptical newspaper editor in Kolchak: The Night Stalker—a cult classic horror-detective series that later inspired The X-Files.

Personal Life and Passions

Behind the scenes, Simon Oakland was known as a private and thoughtful man, deeply devoted to his family and his craft. He married Lois Lorraine Porta, a union that endured despite the pressures of Hollywood. Together, they had one daughter, Barbara, who remained close to her father throughout his life.

Oakland’s first love—music—never left him. He continued to play the violin privately, often as a way to unwind from the emotional demands of acting. Friends described him as a man of “great intellectual curiosity,” who read widely and maintained strong opinions about politics, literature, and the changing tides of American culture.

Unlike many actors of his era, Oakland avoided the celebrity spotlight. He valued the work over fame and often said he preferred the “meatier roles” of television and stage to the glitz of film. He mentored younger actors and was respected for his professionalism, sharp mind, and dry sense of humor.

Decline and Death

Simon Oakland continued acting into the early 1980s, though health issues began to take their toll. Even as his roles became less frequent, he remained a steady presence on TV screens.

He died on August 29, 1983, just one day after his 68th birthday, in Cathedral City, California. The cause was colon cancer, a diagnosis he had kept private until his final months. His passing was mourned by colleagues and fans who recognized him as one of the most consistent and underrated performers of his generation.

Legacy

Simon Oakland’s legacy rests on his ability to breathe life into characters of authority, ambiguity, and conflict. He had a rare gift for making even the smallest role unforgettable. Though never a traditional leading man, he became an essential figure in American film and television history—a character actor of the highest caliber.

Today, his work in Psycho, West Side Story, and Kolchak endures, and his voice and face remain instantly recognizable to generations of film lovers. Quietly brilliant, immensely skilled, and always professional, Simon Oakland left behind a body of work that continues to resonate decades after his death.

Physical Features

- Height: Around 6′ 0″ (183 cm)

- Build: Broad-shouldered and solidly built—perfectly suited for the many roles as cops, generals, detectives, and other commanding figures

- Hair Color: Dark brown to black

- Eye Color: Brown

Though weight and detailed measurements aren’t documented, his large, muscular physique, combined with neatly kept dark hair and warm brown eyes, gave him a classic, authoritative look. This strong, understated physicality became a cornerstone of his performances—silent but unmistakably commanding.

Simon Oakland Tribute

Simon Oakland’s Acting Style: A Force of Controlled Intensity

Simon Oakland was a master of controlled authority, a character actor whose presence on screen often exceeded that of the leads. He built a reputation not on flamboyance or sentimentality, but on clarity, weight, and truth. His acting style can best be described as grounded, intense, and intellectually charged, with a subtle emotional undercurrent that gave his often-stoic characters surprising depth.

Gravitas and Presence

Oakland had a natural gravitas—the kind of presence that made viewers sit up and listen when he entered a scene. This wasn’t just due to his deep, resonant voice (although that was a powerful tool in his arsenal); it was the way he carried himself. He moved with purpose and restraint, often portraying military men, detectives, judges, or psychiatrists—not because he was typecast, but because he was believable in those roles. He radiated command, even in silence.

Voice as Instrument

His voice was perhaps his most distinctive feature. Gravelly, deliberate, and full of tension, it was perfectly suited to delivering long, morally weighted speeches—as seen in his closing monologue in Psycho (1960), where he explains Norman Bates’ psyche. He didn’t rush dialogue. Instead, he let words settle, using well-timed pauses and vocal modulation to draw the viewer in. His voice didn’t just narrate the story—it anchored it.

Controlled Emotion Beneath Stoicism

Though often cast in rigid or tough roles, Oakland never allowed those characters to become wooden. He portrayed emotional suppression rather than absence. A scowl might hide a flicker of uncertainty. A rigid posture might betray moral conflict. He had a gift for showing what a man was holding back, not just what he was expressing. His performances often carried the feeling of a storm beneath the surface—a quality that made him compelling in films like I Want to Live! or Bullitt.

Intelligence and Inner Life

Oakland’s characters always seemed intelligent—even when morally compromised. He played men who weighed their decisions, measured their words, and carried burdens they didn’t always name. This intellectual dimension made him perfect for roles like psychiatrists (Psycho), military commanders (Baa Baa Black Sheep), or conflicted authority figures (Chato’s Land). You never doubted that his characters had lived lives off-screen; he filled them with a sense of history and personal philosophy.

Minimalism in Motion

Physically, Oakland was a minimalist. He didn't over-gesture, rarely raised his voice unnecessarily, and seldom resorted to theatricality. Instead, his power came from stillness. A sidelong glance, a deliberate turn, or a raised eyebrow could shift the entire tone of a scene. This economy of movement gave him great power in ensemble casts—he could do more by doing less.

Unsentimental, Yet Human

Even when playing hard or cynical men, Simon Oakland avoided coldness. His performances rarely sought sympathy, but often invited it anyway. He allowed you to see the weariness behind the badge, the principle behind the gruffness, or the self-doubt behind the authority. He didn’t manipulate emotion—he embodied humanity in men who didn't speak about their feelings.

Consistency and Integrity

Perhaps most admirable was Oakland’s consistency. Over a career spanning nearly three decades, he never gave a lazy performance. Whether in a big-budget film (West Side Story), a TV episode (The Rockford Files), or a B-Western, he brought the same craft, rigor, and truthfulness. He was the kind of actor that directors could trust implicitly—he elevated material, no matter how routine.

In Summary

Simon Oakland’s acting style was:

- Authoritative without bluster

- Emotionally rich without melodrama

- Vocally resonant and rhythmically precise

- Physically understated but full of tension

- Intellectually and morally textured

He was not the star you cheered for. He was the man you listened to—the one who brought truth, doubt, and consequence into the scene. And that’s what made him unforgettable.

Iconic Film Dialogues with Simon Oakland

Psycho (1960) – Dr. Fred Richman’s Closing Monologue

One of his most chilling and unforgettable performances—his final speech explains Norman Bates’s fractured psyche:

“No. I got the whole story — but not from Norman. I got it — from his mother. Norman Bates no longer exists. He only half‑existed to begin with. And now, the other half has taken over. Probably for all time.”

He continues in the same monologue:

“Like I said… the mother… Now to understand it the way I understood it, hearing it from the mother… that is, from the mother half of Norman's mind… you have to go back ten years…”

These lines showcase Oakland’s precise pacing, cool yet commanding tone, and ability to anchor suspenseful scenes.

West Side Story (1961) – Lt. Schrank

In this iconic musical-drama, he delivered a terse rebuke to the street gangs:

“Oh, yeah, sure, I know: It’s a free country and I ain’t got the right… But I got a badge. Whaddaya you got?”

Another sharp exchange:

“Why don’t you get smart, you stupid hooligans? I oughta take you to the station and throw you in the can right now.”

These lines reflect his authoritative, no-nonsense persona, and highlight his knack for gritty, concise delivery.

From Kolchak: The Night Stalker (1974)

In interviews, Oakland made his approach to work and career clear:

“I do my work as an actor and let the big boys worry about it. I do the best I can with the material I have.”

“I go anywhere there’s work.”

These quotes offer insight into his practical, grounded professionalism—unconcerned with ratings or fame, focused on doing solid work wherever it took him.

Awards and Recognition

Simon Oakland, despite a prolific career spanning stage, film, and television, did not receive any major awards or nominations such as Oscars, Emmys, or Golden Globes.

Why No Awards?

- Character actor status: Oakland excelled in supporting and character roles, which often lie outside awards spotlight.

- Strength in ensemble and television: Much of his acclaim came from performances in ensemble films like West Side Story, high-profile dramas like Psycho, and TV series, but major awards at the time tended to focus on lead roles or film-centric achievements.

Critical and Cultural Recognition

Though never formally honored, Simon Oakland's reputation was built on:

- His memorable contributions to iconic films—from Psycho to Bullitt and The Sand Pebbles.

- A substantial television body of work, notably in cult series like Kolchak: The Night Stalker and recurring roles on The Rockford Files and Hawaii Five-O.

- Industry respect, often cited by colleagues and critics for bringing consistency, depth, and authority to every performance.

Legacy Beyond Awards

Oakland's true recognition lies in the lasting cultural and stylistic impact of his work:

- His voice and monologue in Psycho remain among the most analyzed character pieces in cinema.

- His performances have continued to resonate in retrospectives, cult followings, and career-spanning appreciations.

- He is frequently cited in discussions of top-tier character actors, admired for his professionalism and unforgettable presence.

Simon Oakland Movies

1955

- The Desperate Hours – Indiana state trooper (uncredited). A tense thriller about a family held hostage by escaped convicts.

1958

- I Want to Live! – Edward S. “Ed” Montgomery, reporter. Based on Barbara Graham's true story, a gripping courtroom drama examining the death penalty, where Oakland plays the dogged press investigator.

- The Brothers Karamazov – Mavrayek. Epic adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s novel, centered on patricide and moral turmoil in 19th-century Russia.

1959

- The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond – Lieutenant Moody. A crime drama chronicling the life of Depression-era gangster Jack “Legs” Diamond.

1960

- Murder, Inc. – Detective Sgt. William Tobin. A dramatized look at the notorious organized crime enforcement squad operating in the ’30s and ’40s.

- Who Was That Lady? – Belka. A comedy-thriller about a mild-mannered college professor who leads a double life as a spy.

- Psycho – Dr. Fred Richman. In Hitchcock’s horror classic, Oakland delivers the closing monologue explaining Norman Bates’ split personality.

1961

- West Side Story – Lieutenant Schrank. In this musical tragedy inspired by Romeo and Juliet, Oakland plays the hard-nosed cop striving to maintain order amid gang rivalry.

1962

- Follow That Dream – Nick. A lighthearted musical starring Elvis Presley as a man homesteading in Florida, with Oakland in a supporting law-enforcement role.

- Hemingway’s Adventures of a Young Man – Joe Boulton. Coming-of-age tale adapted from Ernest Hemingway’s stories featuring a journey of self-discovery.

- Third of a Man – Doon. A dramatic exploration of political intrigue and moral challenges.

1963

- Wall of Noise – Johnny Papadakis. A gritty story about horse racing and the people bound by it.

1965

- The Satan Bug – Tasserly. A sci‑fi thriller about a stolen biological weapon capable of mass destruction.

1966

- Chubasco – Laurindo. A drama set among surfing culture in California.

- The Plainsman – Chief Black Kettle. A Western retelling of Wild Bill Hickok's story, with Oakland as the portrayed chief.

- The Sand Pebbles – Stawski. Epical wartime drama in 1920s China; Oakland plays a loyal sailor aboard a gunboat.

1967

- Tony Rome – Rudy Kosterman. A detective noir featuring Frank Sinatra, where Oakland plays a crime figure tangled in the mystery.

1968

- Bullitt – Captain Sam Bennett. A landmark action-thriller starring Steve McQueen; Oakland portrays McQueen’s superior in a high-stakes investigation.

1970

- On a Clear Day You Can See Forever – Dr. Conrad Fuller. A musical-fantasy starring Barbra Streisand, exploring reincarnation and psychiatry.

1971

- Scandalous John – Barton Whittaker. A family Western-comedy about a retired bank robber and a mechanically clever horse.

- The Hunting Party – Matthew Gunn. A violent Western with Gene Hackman and Oliver Reed, chronicling a brutish posse.

1972

- Chato’s Land – Jubal Hooker. A stark Western about a half-Native American veteran’s revenge against racist vigilantes.

1973

- Happy Mother’s Day, Love, George – Sheriff Roy. An intense drama focusing on the legal and emotional fallout of a suspicious death.

- Emperor of the North Pole (also Emperor of the North) – Policeman. A Depression-era tale of hobos versus a train conductor, with Oakland cast in law enforcement.

1979

- Drive, Lady, Drive – Bruno. A crime thriller about a cab-driving ex-con involved in a web of mystery and danger.