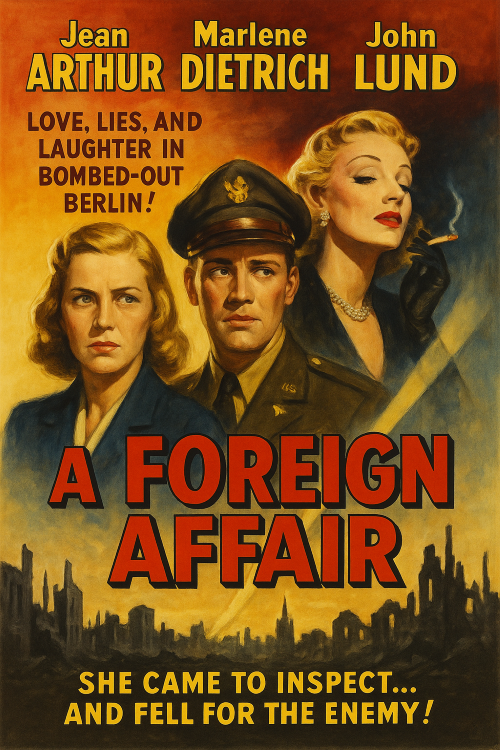

A Foreign Affair - 1948

back| Released by | Paramount Pictures |

| Director | Billy Wilder |

| Producer | Charles Brackett |

| Script | Billy Wilder, Charles Brackett, and Richard L. Breen |

| Cinematography | Charles Lang |

| Music by | Friedrich Hollaender (songs sung by Marlene Dietrich) Score by Robert Emmett Dolan |

| Running time | 116 minutes |

| Film budget | $1.8 million |

| Box office sales | $2.6 million |

| Main cast | Jean Arthur - Marlene Dietrich - John Lund - Millard Mitchell |

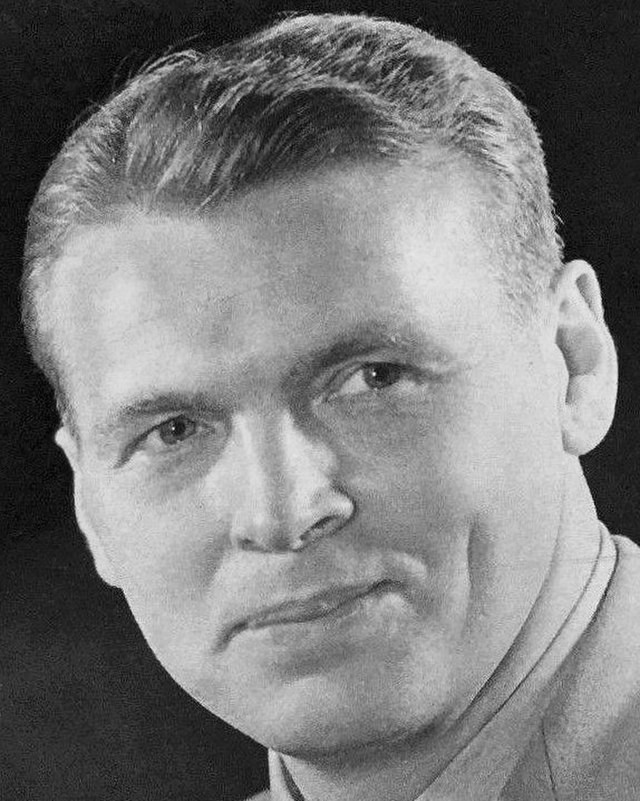

Billy Wilder

A Cynical Romance in the Rubble of Postwar Berlin

A Foreign Affair (1948), directed by Billy Wilder, is a sharp romantic satire set in postwar Berlin. It follows straight-laced Congresswoman Phoebe Frost (Jean Arthur) as she investigates American military conduct, only to become entangled in a love triangle with cynical Captain John Pringle (John Lund) and Erika von Schlütow (Marlene Dietrich), a glamorous former Nazi cabaret singer.

Blending comedy with political critique, the film explores moral ambiguity, survival, and postwar disillusionment. Wilder’s use of on-location shooting in bombed-out Berlin adds gritty realism to the romance and satire. Though controversial at the time for its tone and subject matter, the film is now praised for its boldness, wit, and layered performances—especially from Arthur and Dietrich.

A Foreign Affair stands as a daring example of Hollywood confronting the ethical complexities of occupation, war guilt, and American idealism.

Related

Billy Wilder – 1948

Summary of A Foreign Affair (1948)

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the city of Berlin lies in ruins, both physically and morally. Amid this backdrop, a delegation of American Congressmen and Congresswomen arrives to inspect the conditions of the occupying forces and determine whether American soldiers are upholding proper standards in the devastated city.

Among them is Congresswoman Phoebe Frost (Jean Arthur) from Iowa, a straight-laced, patriotic, and deeply idealistic woman who represents the Midwestern sense of moral integrity. She’s shocked by what she finds in Berlin: a black market, war-weary soldiers, and American officers engaging in questionable relationships with German women. Her shock intensifies when she hears rumors about Erika Von Schlütow (Marlene Dietrich), a sultry former Nazi cabaret singer who appears to be living comfortably under the protection of an American officer.

Phoebe becomes determined to find out which officer is shielding Erika. Her investigation leads her to Captain John Pringle (John Lund), a suave and morally flexible officer from her own home state. Unknown to Phoebe, Pringle is Erika’s lover, and he tries to mislead Phoebe to keep the affair hidden. However, to deflect suspicion, he pretends to court Phoebe—only to find himself genuinely falling for her.

This romantic triangle unfolds against a politically charged background. Erika, despite her past ties to high-ranking Nazis, is trying to survive through charm and manipulation. Pringle is caught between duty, guilt, and desire. Phoebe, who arrives in Berlin with strict moral clarity, is gradually drawn into a more complex and ambiguous world where black and white ethics don’t easily apply.

Analysis

Themes

- Moral Ambiguity:

The central theme of A Foreign Affair is the blurred line between right and wrong in a postwar context. Billy Wilder critiques the rigid moralism of American postwar politics through Phoebe’s character and shows how reality on the ground is much more complex. The film suggests that virtue can sometimes be naive, and corruption can sometimes be a means of survival. - Corruption and Survival:

Erika embodies the gray zone of postwar ethics. She is seductive, manipulative, and possibly complicit in war crimes, but she is also a survivor. Wilder, an Austrian-born Jew who fled the Nazis, shows an ambivalent attitude toward German women like Erika—condemned, yet humanized. - Romantic Cynicism:

Like many of Wilder’s works, romance in A Foreign Affair is laced with irony and compromise. Love is tangled with power, manipulation, and even political interests. Yet, the film allows room for sincerity, particularly as Pringle begins to wrestle with his conscience and feelings for Phoebe.

Character Dynamics

- Phoebe Frost is a stand-in for American innocence and virtue, but her character arc reveals the limitations of rigid ethical judgment. Her transformation throughout the film illustrates how exposure to complexity softens but doesn’t entirely erase idealism.

- Erika Von Schlütow is the film’s most fascinating figure—cool, commanding, and morally ambiguous. She sings haunting cabaret songs that reflect the city's devastation, and her very presence is a reminder of Berlin's cultural and political history.

- John Pringle is the quintessential Wilder male: charming, morally slippery, but capable of growth. He’s not a villain, but an embodiment of the compromises that war demands.

Stylistic Notes

- Cinematic Realism:

Wilder shot the film on location in Berlin, using real ruins, which lends the film a powerful sense of authenticity. The juxtaposition of romantic comedy with documentary-like war devastation is one of the film’s most daring achievements. - Tone and Genre Mixing:

A Foreign Affair balances satire, romance, and political commentary. Wilder walks a fine line, using sharp dialogue and situational irony to expose hypocrisies in both American policy and German complicity. - Music and Symbolism:

The songs performed by Marlene Dietrich, especially “Black Market” and “Illusions,” serve both as diegetic entertainment and thematic commentary. Her voice becomes a kind of lament for the lost soul of a city.

Conclusion

A Foreign Affair is a rich, layered film that uses romance and comedy to explore serious political and moral issues. It exemplifies Billy Wilder’s talent for blending wit with cynicism, character depth with biting social commentary. While it may appear to be a wartime love triangle on the surface, underneath lies a critique of postwar American hypocrisy, a meditation on guilt and survival, and a portrait of human resilience in the wreckage of history.

It’s one of the earliest American films to directly confront the aftermath of WWII in Germany, and remains a bold, nuanced, and enduringly relevant work.

Full Cast – A Foreign Affair

- Jean Arthur as Congresswoman Phoebe Frost

- Marlene Dietrich as Erika Von Schlütow

- John Lund as Captain John Pringle

- Millard Mitchell as Colonel Rufus J. Plummer

- Peter von Zerneck as Hans Otto Birgel

- Stanley Prager as Sergeant Finnegan

- William Murphy as Lieutenant Morrison

- Raymond Bond as Senator James Giffin

- Boyd Davis as Senator Harvey

- Robert Malcolm as Major Ridgley

- Marion Marshall as Fraulein in Cafe

- Frederick Giermann as German Professor

- Harry Hayden as Congressman Jenks

- George E. Stone as M.P. on jeep (uncredited)

- Frank Fenton as Military Police Captain (uncredited)

- Henry Rowland as German Interrogation Officer (uncredited)

- Erich von Stroheim Jr. as German Soldier (uncredited)

- Clem Bevans as Iowa farmer (uncredited)

- Wilton Graff as Congressman (uncredited)

- Arthur Space as Congressman (uncredited)

Trailer of A Foreign Affair

Analysis of Billy Wilder’s Direction

Billy Wilder’s direction in A Foreign Affair is a masterclass in tonal balance, thematic subtlety, and narrative layering. Known for his sharp wit and deep cynicism, Wilder crafts a film that operates simultaneously as a romantic comedy, political satire, and postwar moral drama, all while navigating the ruins—literal and psychological—of a defeated Berlin.

Tone: A Tightrope Walk Between Comedy and Tragedy

One of Wilder’s boldest achievements is how he juxtaposes light romantic comedy with the grim realities of postwar Europe. Many directors would have struggled to maintain coherence in a film that shifts from sly flirtations to bombed-out buildings, from witty banter to references to Nazi war crimes—but Wilder handles this with elegant precision.

- He never allows the romance or comedy to become trivial.

- Nor does he let the political backdrop become overbearing or didactic.

- Instead, these elements interact with and undercut one another, creating a tone that feels unsettling yet truthful—both entertaining and sobering.

Characterization and Direction of Performances

Wilder was famous for drawing nuanced performances out of actors, and in A Foreign Affair, he directs three very different performers to perfection:

- Jean Arthur, in her final starring film role, is guided to express both rigidity and vulnerability. Under Wilder’s direction, her portrayal of Phoebe Frost transforms from caricature to deeply human.

- Marlene Dietrich, already iconic, is not merely used for her glamour. Wilder allows her to become a symbol of defeat, seduction, and survival. Her songs, body language, and world-weary eyes communicate volumes.

- John Lund, the least known of the trio, is molded into a believable embodiment of the American officer who is neither hero nor villain—just tired, conflicted, and trying to get by.

Wilder guides these characters through emotional terrain that feels authentic and ethically complex, never pushing them into melodrama.

Visual Style and Realism

Wilder’s decision to shoot on location in Berlin was both daring and essential. Rather than build stylized sets, he placed his American characters amid real ruins, capturing the shell-shocked, disoriented look of a city recovering from catastrophe.

- The rubble, collapsed buildings, and shadows are not just background—they are part of the emotional landscape of the film.

- This visual realism grounds the satire, giving the humor a sharp, sometimes painful edge.

Wilder’s regular cinematographer, Charles Lang, helps him shape this vision with soft noir lighting, blending realism with touches of classic Hollywood gloss—particularly in scenes featuring Dietrich, who is lit with careful reverence, in contrast to the harsher environments around her.

Political Sophistication and Moral Ambiguity

Wilder was never afraid to criticize hypocrisy, and in A Foreign Affair, he critiques both American self-righteousness and German complicity.

- He exposes the contradictions of American occupation: the U.S. wants to restore order and morality but also turns a blind eye when soldiers fraternize with former enemies.

- Erika’s character is central here—Wilder doesn’t excuse her Nazi past, but he also refuses to reduce her to a symbol of evil. He lets her be human, wounded, self-serving, and charismatic.

Wilder, a Jewish émigré who fled Nazi Germany, brings a deeply personal sensitivity to this moral landscape. His direction suggests: there are no clean hands in war—and fewer still in its aftermath.

Pacing and Dialogue

The film moves with the briskness typical of classic studio-era comedies, but Wilder controls the rhythm carefully. He uses:

- Snappy dialogue (co-written with Charles Brackett and Richard Breen) to keep scenes sharp.

- Longer, more contemplative moments when characters are alone, especially Erika, to give emotional depth.

- Songs as narrative pauses, especially Dietrich’s haunting cabaret numbers, which function like Greek choruses—commenting on the action and setting the mood.

Conclusion: A Director at the Height of His Powers

Billy Wilder’s direction in A Foreign Affair is bold, precise, and deeply layered. He uses comedy not to soften serious issues, but to expose them. His ability to blend the romantic with the political, the satirical with the tragic, and the glamorous with the grim gives the film its enduring impact.

Rather than deliver a neat moral message, Wilder invites the viewer into a morally compromised world where everyone—congresswoman, soldier, cabaret singer—is doing what they can to survive. The result is not just a remarkable film, but a remarkable act of storytelling, where every directorial choice enhances complexity rather than simplicity.

Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair: A Study in Controlled Transformation

Jean Arthur, known for her sparkling voice, comedic timing, and portrayals of morally upright women in Frank Capra films like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, brings a uniquely layered, restrained brilliance to her role as Congresswoman Phoebe Frost in A Foreign Affair. Under Billy Wilder’s direction, Arthur gives one of her most mature, nuanced performances—one that subtly critiques the very type of character she was known for playing.

Moral Rigor Meets Human Vulnerability

At first glance, Arthur’s Phoebe Frost is almost a parody of American righteousness:

- She arrives in Berlin with a stiff spine, conservative dress, and a literal cake from Iowa for a soldier from her district—a comic symbol of her naïve wholesomeness.

- Her clipped speech, upstanding posture, and stern facial expressions all reinforce this upright image.

But as the story unfolds, Arthur delicately unlocks the layers of this seemingly rigid character. She never abandons Phoebe’s essential sense of morality, but she begins to shade it with discomfort, doubt, curiosity—and even desire.

The brilliance of Arthur’s performance lies in how subtly she allows these shifts to occur. In the early scenes, her comedy is crisp and mechanical, emphasizing Phoebe’s lack of adaptability. As the character is emotionally confronted—by the ruins of Berlin, by Erika’s cynical elegance, and by Pringle’s charm—Arthur softens. Her voice slows, her body language opens up, and her eyes begin to show conflict. Yet she never lets Phoebe fall completely into romantic surrender or political compromise.

Comedic Precision with Emotional Undercurrent

Arthur’s gift for comedy remains intact here, but Wilder pushes it into deeper emotional territory. Her facial reactions—exaggerated just enough to be funny—are also tools for revealing Phoebe’s internal struggle:

- Her look of disapproval upon entering a cabaret club filled with soldiers and German women isn’t just moral outrage—it’s the pain of seeing ideals collapse in real time.

- Her discomfort when Pringle begins to woo her feels simultaneously comic and tragic: this is a woman who has likely never been romantically pursued in such a way, and Arthur communicates both flattery and panic with microscopic detail.

Even her physical comedy—walking stiffly through ruins, struggling to maintain her dignity—has an added poignancy in the context of a world turned upside down.

Sparring with Dietrich: A Study in Contrast

One of the most fascinating aspects of Arthur’s performance is how it plays against Marlene Dietrich’s Erika von Schlütow. Wilder uses the two actresses as emblems of contrasting worlds:

- Arthur: upright, awkward, idealistic, rooted in small-town American virtue.

- Dietrich: slinky, cosmopolitan, weary, seductive, and ambiguous.

Arthur holds her own in their shared scenes by doubling down on her stiffness, which serves both as comic armor and as a form of resistance. She never tries to out-seduce Dietrich (which would be futile)—instead, she evolves Phoebe into a more emotionally courageous woman, which gives her a kind of strength Dietrich’s Erika doesn’t have.

A Performance Tinged with Melancholy

Behind Arthur’s control is a trace of melancholy—partly because the role demands it, and partly because A Foreign Affair marked the end of her film career. She reportedly clashed with Wilder during filming and felt uncomfortable on set, but none of that turmoil shows in her performance. Instead, it lends Phoebe an additional layer: the sense that she’s clinging to values and behaviors that no longer quite fit the world she’s been dropped into.

By the final act, when Phoebe confronts Pringle and Erika, Arthur plays her not as someone broken or converted, but as someone disillusioned yet still principled, having earned a harder, deeper understanding of what morality costs.

Conclusion: A Controlled, Complex, and Understated Triumph

Jean Arthur’s performance in A Foreign Affair is a masterclass in restraint and evolution. Rather than relying on dramatic transformation or sentimental flourishes, Arthur allows Phoebe Frost to change in small, deeply human ways. The performance is marked by control, intelligence, and a quiet emotional power—especially poignant because it signaled the end of an era for Arthur, who retired from film shortly afterward.

It’s a performance that grows richer with age, much like the film itself: not loud or showy, but precise, principled, and ultimately unforgettable.

Important Film Quotes

Congresswoman Phoebe Frost (Jean Arthur):

"I came to Berlin to investigate the morale of the troops, not to ruin it!"

This line humorously captures Phoebe's initial uptight idealism—and Wilder’s satirical take on American moralism in a morally shattered city.

Erika Von Schlütow (Marlene Dietrich):

"In the black market, the heart beats faster."

A classic line dripping with irony and seduction, it sums up Erika’s character and the tone of postwar Berlin, where survival trumps sentiment.

Captain John Pringle (John Lund):

"You can’t just stamp ‘morale’ on a crate and ship it over."

A sardonic jab at the idea that American values can be exported wholesale, reflecting Wilder’s skepticism toward American interventionism.

Erika Von Schlütow (singing “Illusions” in the cabaret):

"Illusions, you give me illusions, that fill my empty days..."

Dietrich sings this haunting number with a look of weary detachment. It's not just a song—it’s a summary of the film’s themes: disillusionment, emotional survival, and moral fatigue.

Phoebe Frost (to Pringle):

"You’re a disgrace to your uniform."

Delivered with indignation early in the film, this quote encapsulates Phoebe’s initial black-and-white worldview.

Erika Von Schlütow (to Phoebe):

"The world is not a cornfield in Iowa."

A biting reminder to Phoebe that global affairs—and human behavior—are more complex than small-town values allow.

Col. Plummer (Millard Mitchell):

"We’re not here to reform them. We’re here to prevent a Third World War."

A surprisingly candid line that underscores the practical, often morally compromising goals of postwar occupation.

John Pringle (about Erika):

"She’s like a lovely old building that’s been bombed inside."

This poetic metaphor hints at the damage Erika carries and the lingering emotional fallout of the war.

Notable Movie Scenes

The Cabaret Scene – Erika Sings “Black Market”

Why it’s classic:

This early scene introduces Marlene Dietrich’s Erika in a smoky Berlin nightclub, singing “Black Market” to a room full of American GIs and German civilians. It’s not just a musical performance—it’s a powerful commentary on the war's aftermath and the economy of survival.

- Dietrich’s presence is magnetic—both weary and defiant.

- Wilder lingers on the reactions of the audience, including Phoebe Frost, watching in growing discomfort.

- The lyrics themselves (“You’d be surprised what you can buy on the black market”) are sly, darkly humorous, and deeply political.

Impact:

It sets the tone for the film’s moral complexity and casts Erika as both a seductress and a survivor in the gray moral landscape of postwar Berlin.

Phoebe’s Cake Scene – From Innocence to Shock

Why it’s classic:

Congresswoman Phoebe Frost, carrying a cake from Iowa to deliver to a soldier from her district, is introduced in a moment that’s comedic and symbolic.

- She moves through the wreckage of Berlin with Midwestern decorum, completely out of place.

- The cake, a symbol of small-town virtue, becomes absurd in this world of corruption and rubble.

Impact:

Wilder uses this scene to instantly establish the contrast between American moral idealism and European postwar cynicism, setting up Phoebe’s transformation throughout the film.

Erika and Phoebe Confrontation Scene

Why it’s classic:

In one of the film’s most charged scenes, Phoebe confronts Erika Von Schlütow about her relationship with Captain Pringle—and Erika answers with cool, calculated elegance.

- The dialogue is sharp and layered with subtext.

- Erika delivers a brutal line: “The world is not a cornfield in Iowa.”

- The power dynamics shift rapidly between the two women—Phoebe, representing moral law, and Erika, representing practical survival.

Impact:

It’s a battle of ideologies, class, and gender, all within the intimate space of female rivalry and political power.

John Pringle’s Romantic Deception

Why it’s classic:

Captain Pringle begins to court Phoebe to cover up his ongoing relationship with Erika—but as his feelings shift, the comedy becomes more tangled and emotionally interesting.

- The humor is situational and character-driven—especially when Pringle’s lies begin to unravel.

- Wilder directs these scenes with restraint, allowing the emotional stakes to grow without melodrama.

Impact:

This sequence deepens Pringle’s character and adds to the moral ambiguity: is he sincere or still manipulating? Wilder leaves it ambiguous until near the end.

Erika Sings “Illusions” – A Haunting Interlude

Why it’s classic:

Later in the film, Erika performs the song “Illusions” in the cabaret—a melancholic, smoky ballad about disillusionment.

- Dietrich sings with a tired, almost broken sensuality.

- The performance is deeply symbolic: Berlin itself is full of broken illusions—of empire, of victory, of love.

- Wilder cuts between Erika and the watching characters, particularly Pringle, whose guilt becomes palpable.

Impact:

This scene functions as a moral heartbeat of the film, showing the emotional and psychological damage war has wrought, especially on those like Erika who have had to reinvent themselves to survive.

The Final Jeep Scene

Why it’s classic:

In a somewhat lighter but telling conclusion, Phoebe and Pringle drive off together in a jeep, now on more equal footing—though not without Wilder’s signature ambiguity.

- It’s not a grand romantic finale but a subtle acknowledgment of growth and compromise.

- Wilder resists a “clean” resolution—morality has been tested, and love is possible, but nothing is pure.

Impact:

The scene is emblematic of Wilder’s worldview: relationships are messy, redemption is partial, and clarity is hard-won.

Awards and Nominations for A Foreign Affair

Academy Awards (Oscars) – 1949

Nominated:

- Best Writing, Screenplay

– Billy Wilder, Charles Brackett, Richard L. Breen

(for original screenplay – recognized for its sharp, witty, and morally complex writing) - Best Cinematography, Black-and-White

– Charles Lang

(noted for the stark, authentic visual portrayal of postwar Berlin) - Best Art Direction-Set Decoration, Black-and-White

– Hans Dreier and John Meehan (Art Direction), Russell A. Gausman and Emil Kuri (Set Decoration)

(for the realistic and detailed set design that blended actual Berlin ruins with constructed interiors)

Other Recognition

While A Foreign Affair did not win any Oscars, it has received critical acclaim over time and is now widely regarded as one of Billy Wilder’s more underrated films—especially notable for its bold political subject matter, on-location shooting, and the unique pairing of Jean Arthur and Marlene Dietrich.