Ben-Hur - 1959

back| Released by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

| Director | William Wyler |

| Producer | Sam Zimbalist |

| Script | Screenplay by Karl Tunberg - (Additional contributions from Gore Vidal, Christopher Fry, and Maxwell Anderson, although only Tunberg received official credit) - Based on the 1880 novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ by Lew Wallace |

| Cinematography | Robert L. Surtees (in MGM Camera 65 widescreen process) |

| Music by | Miklós Rózsa |

| Running time | 212 minutes |

| Film budget | $15 million |

| Box office sales | $146 million |

| Main cast | Charlton Heston - Jack Hawkins - Stephen Boyd - Hugh Griffith - Martha Scott - Cathy O'Donnell |

Ben-Hur

An Epic Journey from Vengeance to Redemption

Ben-Hur (1959), directed by William Wyler, is an epic historical drama centered on Judah Ben-Hur, a Jewish prince betrayed by his Roman friend Messala. After years of slavery, Judah returns seeking vengeance, only to find spiritual redemption through the teachings of Christ. The film masterfully blends grand spectacle—highlighted by the legendary chariot race—with a deeply human story of betrayal, faith, and forgiveness.

Its impact was monumental: winning a record 11 Academy Awards, it set new standards for epic filmmaking, practical effects, and emotional storytelling. Ben-Hur became a defining film of Hollywood’s Golden Age, revered for its scale, sincerity, and enduring themes.

Related

Ben-Hur – 1959

Summary

Ben-Hur opens in 1st-century Jerusalem, during the early years of Roman occupation. The central figure is Judah Ben-Hur, a wealthy Jewish prince and merchant. Childhood friends with Messala, a Roman who has recently returned as a commanding officer, Judah is at first delighted by the reunion. However, it quickly becomes clear that their paths have diverged. Messala now serves Roman power with fierce loyalty, while Judah’s allegiance lies with his people. Their ideological conflict climaxes when Judah refuses to betray fellow Jews suspected of dissent.

A tragic accident — a dislodged roof tile during a Roman parade — offers Messala the excuse to destroy Judah’s family. Judah is arrested and sentenced to the galleys, while his mother and sister are imprisoned. Stripped of status, home, and freedom, Judah vows revenge.

On his way to the Roman galleys, Judah experiences a mysterious act of kindness from an unknown man — Jesus of Nazareth — who gives him water when others would not. This moment, though brief, becomes symbolic of the film's larger spiritual undercurrent.

After enduring years as a galley slave, Judah's fortunes change during a sea battle. He saves the life of Quintus Arrius, a Roman commander, and is subsequently adopted by him as a son. Judah returns to Judea a free man, now wealthy and educated in the ways of Rome — but his heart remains set on vengeance.

Back in Jerusalem, Judah learns from Sheikh Ilderim, an Arab horse breeder, that Messala is sponsoring a team in the upcoming chariot race. With the sheikh’s support, Judah enters the race to confront Messala on the track — a confrontation that culminates in one of cinema’s most iconic action sequences. The chariot race is a brutal, balletic duel of wills. Judah wins; Messala, mortally wounded, spitefully reveals that Judah’s mother and sister are alive — but have contracted leprosy.

Judah finds them in the Valley of the Lepers, where they live in hiding. He conceals the truth from Esther, his beloved, who urges him to find a different path than vengeance. At the film’s climax, Judah witnesses the crucifixion of Jesus, the man who once gave him water. As a thunderstorm splits the sky, he realizes the transformative power of grace and forgiveness. His mother and sister are miraculously cured.

Analysis

Themes

Revenge and Redemption

At its core, Ben-Hur is a story of transformation. Judah begins his journey seeking justice but is consumed by vengeance. This personal vendetta drives much of the narrative tension — but the film refuses to end on revenge. Instead, it moves beyond retribution toward forgiveness and healing. The final scenes, tied to Christ’s death, signal the redemptive power of faith and mercy.

Identity and Loyalty

Judah’s internal struggle reflects broader tensions between personal integrity and public allegiance. His fall and rise are not just physical but spiritual. His loyalty to family, faith, and justice remains steadfast, while Messala’s loyalty to Rome blinds him morally and politically. The contrast between these two former friends forms the dramatic core of the film.

Political and Religious Oppression

The film does not shy away from depicting the cruelty of the Roman Empire. Judah’s suffering in the galleys and his family’s imprisonment highlight the oppressive machinery of imperial power. Yet the quiet, persistent presence of Jesus introduces a countercurrent — one of peace, dignity, and moral resistance.

Cinematic Achievements

Chariot Race

The chariot race is a technical marvel, even by today’s standards. It was filmed over five weeks with meticulously choreographed stunts and practical effects. No CGI — just dust, sweat, and real horses. This sequence alone has made the film legendary and remains one of the most intense action scenes in film history.

Score by Miklós Rózsa

The music is emotionally rich, sweeping from heroic brass to solemn choral themes. Rózsa’s score enhances both grandeur and intimacy, earning him one of the film’s 11 Academy Awards.

Visual Grandeur

Shot in MGM Camera 65 (a 65mm widescreen format), the film uses its visual scale to great effect — from Roman galley ships to massive crowd scenes. Yet Wyler, known for intimate dramas, brings psychological focus to character interactions, grounding the epic in real emotion.

Legacy

Ben-Hur was not just a critical and commercial triumph — it became the gold standard for biblical and historical epics. It won 11 Academy Awards, a record it held for decades (later tied by Titanic and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King). Its blend of spectacle and spirituality has rarely been matched.

More than a tale of Roman brutality or thrilling races, Ben-Hur is a human story: about loss, identity, revenge — and ultimately, spiritual awakening. In its final scenes, the man who began with rage and sorrow ends in peace, not through conquest but through compassion. That transformation is the film’s true miracle.

Main Cast

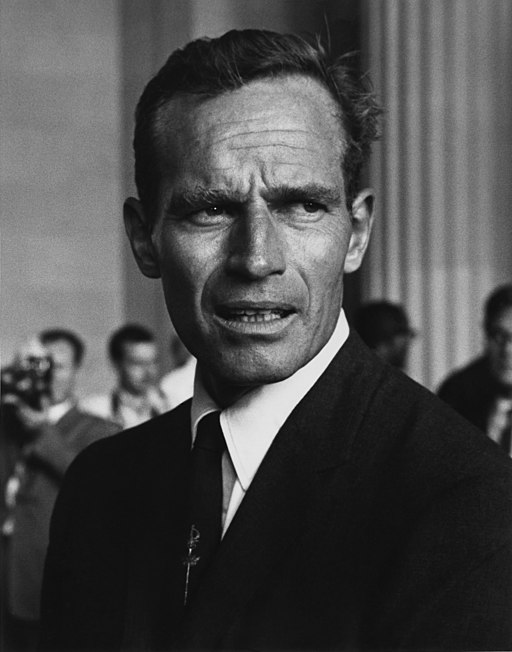

- Charlton Heston – Judah Ben-Hur

- Jack Hawkins – Quintus Arrius

- Stephen Boyd – Messala

- Haya Harareet – Esther

- Hugh Griffith – Sheikh Ilderim

- Martha Scott – Miriam (Judah's mother)

- Cathy O'Donnell – Tirzah (Judah's sister)

- Sam Jaffe – Simonides (Esther’s father)

- Ady Berber – Malik (Ilderim’s servant)

- Finlay Currie – Balthasar

- Frank Thring – Pontius Pilate

- George Relph – Tiberius Caesar (his final film role)

- André Morell – Sextus

- Terence Longdon – Drusus (Messala’s aide)

- Marina Berti – Flavia (Esther’s friend and hostess)

- Robert Brown – Chief rower

- Duncan Lamont – Marius (Roman officer)

Uncredited but Notable Roles

- Claude Heater – Jesus (uncredited, portrayed only from behind or in silhouette)

- Lando Buzzanca – Jewish slave (uncredited)

- Richard Hale – Gaspar (one of the Magi)

- Joe Canutt – Chariot driver and stunt double for Charlton Heston

- May McAvoy – Woman in crowd (uncredited; McAvoy was a silent film star and appeared briefly as a cameo)

Ben-Hur Theatrical Trailer

Where was Ben-Hur Filmed?

Ben-Hur (1959) was filmed primarily in Italy, using some of the largest and most elaborate sets ever constructed at the time. Here’s an overview of the main filming locations:

Cinecittà Studios – Rome, Italy

- The vast majority of the film, including the interiors and many large exterior sets, was shot here.

- MGM built enormous sets on the backlots, including Jerusalem streets, the Roman Forum, and the chariot arena.

Chariot Race Arena – Cinecittà Backlot

- The Circus Maximus set for the chariot race was specially constructed and became the largest film set ever built at that time (18-acre oval).

- It took over a year to build and used thousands of extras.

Mediterranean Sea – Near Livorno, Italy

- Scenes involving the Roman galley and naval battle were shot here, including full-scale sea battle models.

Arcinazzo Romano – Lazio region

- Outdoor scenes depicting Judean countryside and desert regions were filmed here, standing in for ancient Palestine.

William Wyler’s Direction in Ben-Hur: A Study in Epic Intimacy

William Wyler’s direction in Ben-Hur is a masterclass in balancing spectacle with subtlety. Though best known for dramas that focus on complex characters and relationships (The Best Years of Our Lives, Wuthering Heights, Mrs. Miniver), Wyler brought that same emotional precision to the vast and demanding canvas of Ben-Hur. What resulted was not just a historical epic, but a deeply human story set against the backdrop of imperial grandeur and spiritual transformation.

Human Drama at the Heart of the Epic

Though Ben-Hur is filled with colossal sets, grand pageantry, and legendary action sequences, Wyler never loses sight of the personal. He focuses on Judah Ben-Hur’s emotional journey — from nobleman to slave, from victim to victor, from vengeance to redemption. Wyler's background in directing intimate dramas is key here. The emotional weight of Judah’s journey is always clear, even as the world around him shifts from palaces to galleys to desert encampments.

Notably, Wyler emphasizes the expressions and moral choices of characters as much as he does the action. He favors medium shots and close-ups during key emotional moments, allowing the audience to engage with inner turmoil rather than just external conflict.

Control of Tone and Pacing

One of the greatest challenges in directing an epic of this scale is pacing. Wyler masterfully orchestrates the film's rhythm, alternating between moments of high tension (like the sea battle or the chariot race) and moments of quiet reflection (Judah’s reunion with Esther, or his encounter with Christ). He avoids melodrama by trusting silence and restraint.

The length of the film (over 3 hours) never feels bloated, because Wyler uses time to deepen character arcs and allow themes to emerge gradually. Scenes unfold with a patience that invites immersion rather than rush.

The Chariot Race: Controlled Chaos

The chariot race sequence is widely regarded as one of the most brilliantly directed action scenes in film history. Wyler chose not to direct the race personally (that task largely fell to second-unit director Andrew Marton and stunt coordinator Yakima Canutt), but he oversaw the design, flow, and integration of the scene into the story. What distinguishes this sequence isn’t just its technical brilliance, but how Wyler frames it as a narrative climax rather than just a visual set piece.

He prepares the audience emotionally: by the time Judah enters the arena, the stakes are personal and profound. The editing, camera placement, and real danger of live-action stunts bring visceral realism — yet it is Judah’s moral struggle with vengeance that gives the race its true dramatic weight.

Minimalist Depiction of Jesus

Wyler’s decision to never show Jesus’ face is one of the film’s most elegant and powerful directorial choices. Christ is felt more than seen — present in gesture, silence, and kindness. This restraint adds reverence and mystery, contrasting with the roaring violence and power games of Rome. In doing so, Wyler subtly shifts the film’s center of gravity from human power to divine grace, especially in the final scenes.

Command of Production Scale

Wyler was known for his meticulousness, and Ben-Hur was no exception. He insisted on authenticity, pushing the production team to build enormous sets and work with thousands of extras. He personally oversaw casting, rehearsals, and set designs — ensuring that even the largest scenes retained clarity and purpose. Despite the film's vast scope, there is consistency in tone and detail, which speaks to Wyler's rigorous oversight.

Collaboration and Leadership

Directing Ben-Hur was a monumental task — thousands of crew, international actors, multiple units filming simultaneously. Wyler's leadership was steady and collaborative. He worked closely with cinematographer Robert Surtees to use the new widescreen format (MGM Camera 65) to great effect, filling the screen with majestic compositions that never felt crowded. He guided Charlton Heston through one of his career-defining performances, emphasizing internal conflict as much as external presence.

Conclusion: A Director at the Peak of His Powers

William Wyler’s direction in Ben-Hur represents the ideal fusion of classic Hollywood storytelling with modern ambition. He turned a biblical-historical epic into something deeply human and timeless. His command of tone, character, and grandeur made the film not just a box office triumph, but a work of art that continues to resonate across generations.

In Wyler’s hands, Ben-Hur becomes more than a tale of revenge and triumph — it is an exploration of faith, identity, and redemption on the largest canvas imaginable. His direction reminds us that even the greatest epics are, at their core, stories about people.

Charlton Heston as Judah Ben-Hur: A Towering, Layered Performance

Charlton Heston’s portrayal of Judah Ben-Hur is commanding, dignified, and deeply felt. In many ways, Heston was the perfect actor for the role: his physical stature, authoritative voice, and classical presence fit seamlessly into the film’s grand, biblical scale. Yet what elevates his performance beyond the surface of epic heroism is the emotional journey he embodies — from privileged prince to embittered slave, and ultimately to a man transformed by grace.

Physical Presence and Heroic Gravitas

Heston brings an unshakable physicality to the role, necessary for a character who must endure years of hardship and emerge as both a chariot champion and a spiritual seeker. His body becomes part of the story: lean and desperate in the galleys, upright and composed before Arrius, tense and vengeful in Jerusalem.

His movements are always deliberate — never flailing or frantic, even in moments of rage or despair. There’s a regal quality to his carriage, fitting for a prince even when stripped of title and wealth. Heston doesn’t just act as Ben-Hur — he embodies him.

Emotional Depth Beneath the Stoicism

Heston’s acting style is often associated with a kind of noble stoicism, but in Ben-Hur, he finds compelling ways to convey internal conflict. His face, usually so firm and resolute, occasionally flickers with pain, longing, or doubt — particularly in scenes with Esther or when he visits his leprous mother and sister.

One particularly effective moment is Judah’s near-silent breakdown after learning his mother and sister are alive but diseased. Heston says little, but his stillness — the way he looks away, clutches at nothing — speaks volumes. It’s in these quiet, restrained moments that the humanity of the character breaks through the grandeur of the epic.

Evolution of Character

Heston masterfully charts Judah’s transformation from entitled nobleman to vengeful gladiator, and finally to a man capable of forgiveness. Early in the film, his Judah is proud and idealistic, confident in his role within society and his friendship with Messala. After his betrayal, Heston lets that confidence harden into fury and righteous indignation.

But the performance subtly shifts again in the final act. Heston begins to show signs of wear — in posture, tone, and pace — as Judah’s obsession with revenge drains him. His final moments, as he returns home after witnessing Christ’s crucifixion, are deeply affecting. He speaks less and listens more. His shoulders lower. He looks at Esther and his healed family not with triumph, but with humility and wonder. It's an arc of maturity, and Heston carries it with skillful nuance.

Commanding Dialogue Delivery

Heston's voice is one of his greatest assets. He delivers lines with clarity and conviction, but never lapses into theatrical overstatement. His exchanges with Messala (Stephen Boyd) early in the film are particularly sharp — a careful duel of ideology masked in polite tones. Later, his declaration of vengeance is delivered not with melodrama, but with an icy, coiled resolve that makes it even more chilling.

And in contrast, when he speaks to Jesus, or about Him, his tone changes subtly. The grandeur gives way to quiet reverence. It’s a fine adjustment, but it underscores the internal shift taking place within Judah.

Chemistry with Supporting Cast

Heston’s scenes with Stephen Boyd (Messala) are electric. The chemistry between them — once warm, later bitter — gives the film its emotional anchor. Heston also has gentle, believable rapport with Haya Harareet (Esther). He plays the romance with restraint, letting affection bloom not through big declarations but through trust, shared silence, and eye contact.

His scenes with Martha Scott (Miriam) and Cathy O’Donnell (Tirzah) are heartbreaking. Heston shows Judah’s guilt and helplessness not through breakdowns, but through eyes that refuse to meet theirs, or through lines delivered with haunted hesitation.

Conclusion: A Performance Worthy of Legend

Charlton Heston’s performance in Ben-Hur is not merely iconic because of the film’s scale or its Oscars. It is enduring because he carries an entire world on his shoulders, yet never lets the character feel like a myth. Judah Ben-Hur is noble, yes — but he is also bitter, grieving, and searching. Heston channels all these layers into a performance that feels both monumental and deeply personal.

In lesser hands, Judah might have been just a cardboard hero. Under Heston’s portrayal, and Wyler’s direction, he becomes a man for all time — a symbol of endurance, moral struggle, and spiritual awakening.

Important Quotes from Ben-Hur (1959)

Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston):

“I’ll tell you what Rome is. It’s an affront to God!”

— Judah expressing his growing disillusionment with Roman power and its oppression.

“You may conquer the land; you may slaughter the people. But that is not the end — we will rise again.”

— A moment of resistance and defiance toward Messala and Rome.

“I see now I have been praying for the wrong things. I’ve been praying that He would make His will known to me. But He’s done that. He made it known in the life that He lived and the death that He died.”

— Spoken near the end of the film, marking Judah’s spiritual awakening.

Messala (Stephen Boyd):

“You’re either for me or against me.”

— A chilling expression of Messala’s authoritarian worldview and betrayal of friendship.

“The race is not over. It goes on, Judah. And you are alone.”

— Said bitterly in his final moments, still unable to let go of pride and rivalry.

Esther (Haya Harareet):

“It was Judah Ben-Hur I loved — the man who believed in justice, in mercy, in love.”

— Esther’s plea for Judah to abandon revenge and return to his better self.

Sheikh Ilderim (Hugh Griffith):

“There is no law in the arena. Many are killed. I hope to see you again — with your shield.”

— A sardonic but warm-hearted line from Ilderim, foreshadowing the brutal chariot race.

Pontius Pilate (Frank Thring):

“Where there is greatness, there is simplicity.”

— A line with ironic weight, given the context of political power and the presence of Christ.

Narrator (Opening Title):

“In the Year of Our Lord...”

— The film’s framing of the story as one of spiritual as well as historical importance.

Unseen Jesus (silent scenes):

While Jesus has no spoken lines in the film, his presence is profoundly felt — particularly when he gives water to Judah, and again during the crucifixion. These silent acts are among the film’s most powerful “unspoken” statements.

Classic Scenes

Ben-Hur (1959) is filled with unforgettable sequences that have become landmarks in film history — not only for their technical brilliance but also for their emotional depth and symbolic resonance. Below are some of the most classic and iconic scenes from the film, each significant in its own right.

The Chariot Race

Scene Summary:

Set in the Circus Maximus in Jerusalem, the chariot race is the film’s centerpiece. Judah Ben-Hur competes against his former friend-turned-enemy, Messala, in a brutal and deadly contest.

Why it’s iconic:

- One of the most thrilling and realistic action sequences ever filmed — no CGI, just live horses, real dust, and meticulously choreographed stunts.

- The emotional stakes are enormous: this is not just a race, but a confrontation fueled by betrayal, rage, and justice.

- The scene runs for nearly 10 minutes and uses wide-angle, sweeping shots as well as intense close-ups to create visceral tension.

- Judah’s silent resolve vs. Messala’s ruthless aggression is captured in their eyes and posture as much as in the wreckage they cause.

Legacy:

This sequence set a standard for practical action filmmaking and remains one of the most studied scenes in film schools.

Jesus Gives Water to Judah

Scene Summary:

After Judah is condemned to slavery and paraded through the desert, a nameless figure steps forward to give him water — defying a Roman guard. This man is Jesus.

Why it’s iconic:

- Jesus’ face is never shown, in line with William Wyler’s reverent approach, but the emotional power is immense.

- The act of kindness in a moment of despair stays with Judah throughout the film — it’s a spiritual seed that eventually blossoms into transformation.

- The silence, lighting, and expressions make it one of the most poignant moments in the film — a miracle expressed without words.

The Sea Battle

Scene Summary:

Judah serves as a galley slave aboard a Roman warship. When a battle erupts, he defies orders and saves the life of the Roman commander Quintus Arrius.

Why it’s iconic:

- The battle is filmed with dark, thundering intensity — the clash of oars, creaking wood, fire, and drowning slaves create a sense of claustrophobic chaos.

- The moment Judah refuses to accept death and fights for survival is a turning point in his arc.

- His rescue of Arrius earns him freedom, symbolizing the first reversal of his fortune.

Judah Reunites with Esther

Scene Summary:

Judah returns to Jerusalem and reconnects with Esther, the woman he once loved, now changed by time and sorrow.

Why it’s iconic:

- This scene showcases Charlton Heston’s quiet intensity and Haya Harareet’s emotional subtlety.

- The moment reflects how both characters have been shaped by loss, hope, and the passage of time.

- Their reunion is not triumphant but deeply human — filled with longing, caution, and tenderness.

The Discovery of Miriam and Tirzah

Scene Summary:

Judah discovers that his mother and sister are still alive — but afflicted with leprosy and living in exile.

Why it’s iconic:

- One of the film’s most emotionally devastating scenes.

- Heston plays it with restrained grief, while Martha Scott and Cathy O’Donnell show dignity and suffering without melodrama.

- It’s the moment Judah begins to see that revenge alone will not restore what he has lost.

The Crucifixion

Scene Summary:

In the final act, Judah witnesses the crucifixion of Jesus — the same man who once gave him water. As Christ dies, a storm breaks, and his mother and sister are miraculously healed.

Why it’s iconic:

- The spiritual climax of the film.

- The cinematography, music by Miklós Rózsa, and the symbolic cleansing rain come together in an emotionally and visually stunning moment.

- Judah’s transformation is complete — not through violence, but through grace, sacrifice, and healing.

Awards and Recognition for Ben-Hur

Academy Awards (Oscars) – 1960

Ben-Hur received 12 nominations and won 11 Oscars, setting a record at the time (a record later tied by Titanic (1997) and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003)).

Wins (11 Oscars):

- Best Picture – Sam Zimbalist (posthumously)

- Best Director – William Wyler

- Best Actor – Charlton Heston (Judah Ben-Hur)

- Best Supporting Actor – Hugh Griffith (Sheikh Ilderim)

- Best Art Direction – Color – William A. Horning, Edward C. Carfagno, Hugh Hunt

- Best Cinematography – Color – Robert L. Surtees

- Best Costume Design – Color – Elizabeth Haffenden

- Best Film Editing – Ralph E. Winters, John D. Dunning

- Best Sound Recording – Franklin Milton (MGM)

- Best Music – Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture – Miklós Rózsa

- Best Special Effects – A. Arnold Gillespie (visual), Robert MacDonald (visual), Milo B. Lory (sound)

Nomination (1 Oscar – did not win):

- Best Adapted Screenplay – Karl Tunberg

Golden Globe Awards – 1960

Wins:

- Best Motion Picture – Drama

- Best Director – William Wyler

- Best Supporting Actor – Stephen Boyd (Messala)

- Best Original Score – Miklós Rózsa

Nominations:

- Best Actor – Drama – Charlton Heston

BAFTA Awards – 1960 (UK)

Wins:

- Best Foreign Actor – Charlton Heston

Nominations:

- Best Film from Any Source

- Best British Actor – Hugh Griffith

- Best Film – United Nations Award

Directors Guild of America (DGA) Award – 1960

- Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures – William Wyler (Won)

Writers Guild of America (WGA) – 1960

- Nomination: Best Written American Drama – Karl Tunberg

National Board of Review – 1959

- Best Picture

- Top Ten Films of the Year

New York Film Critics Circle Awards – 1959

- Runner-Up: Best Film

- Runner-Up: Best Director – William Wyler

Other Notable Recognitions

- American Film Institute (AFI):

- Ben-Hur consistently appears on AFI's "100 Years" lists:

- #72 on AFI's 100 Greatest American Movies (1998)

- #100 in the 10th Anniversary Edition (2007)

- #2 on AFI's Top 10 Epics (behind Lawrence of Arabia)

- Judah Ben-Hur ranked among AFI’s 50 greatest movie heroes

- Ben-Hur consistently appears on AFI's "100 Years" lists:

- National Film Registry (U.S. Library of Congress):

- Selected for preservation in 1997 for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”