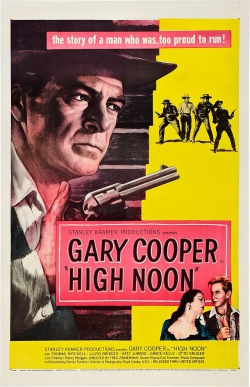

High Noon - 1952

back| Released by | United Artists |

| Director | Fred Zinnemann |

| Producer | Stanley Kramer |

| Script | Carl Foreman (based on the short story |

| Cinematography | Floyd Crosby (black-and-white) |

| Music by | Dimitri Tiomkin (Including the Oscar-winning song |

| Running time | 85 minutes |

| Film budget | $730,000 |

| Box office sales | $12 million |

| Main cast | Gary Cooper - Grace Kelly - Thomas Mitchell - Lloyd Bridges - Katy Jurado |

High Noon

A Lone Man stands for Justice while the World Turns Away

High Noon (1952) is a real-time Western about Marshal Will Kane, who faces a deadly outlaw returning to town at noon. Though newly married and retired, Kane chooses to stay and confront the threat, only to find himself abandoned by the townspeople he once protected. As the clock ticks down, he stands alone, embodying courage in the face of fear and moral failure.

Directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Gary Cooper in an Oscar-winning role, the film broke genre conventions with its psychological tension, moral complexity, and minimalist style. Often seen as an allegory for McCarthyism, High Noon challenged Hollywood norms and became a timeless study in integrity and civic responsibility. Its influence extends far beyond the Western, shaping modern suspense storytelling and redefining the lone hero archetype.

Related

High Noon – 1952

Summary

Set in the small town of Hadleyville in the New Mexico Territory, High Noon unfolds in near real-time on a single, sweltering Sunday. The story begins as Marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper), a longtime peacekeeper of the town, has just married Amy Fowler (Grace Kelly), a pacifist Quaker, and plans to retire and leave town to start a new life. But moments after the wedding, Kane receives alarming news: Frank Miller, a violent outlaw he had arrested years earlier, has been released from prison and is arriving on the noon train, seeking revenge.

Miller’s gang—three men led by his brother—wait at the station for his arrival. Though advised to leave town immediately, Kane’s sense of duty and justice prevents him from running. He feels morally bound to protect the town that had once supported him. He tears off his wedding clothes, puts his badge back on, and begins a desperate search for deputies willing to stand with him.

However, as Kane goes from person to person—including friends, town leaders, and even the church congregation—he faces rejection, fear, and cowardice. Some townspeople don’t want to get involved. Others blame Kane for disturbing the peace. Even his former deputy, Harvey Pell (Lloyd Bridges), refuses to help unless he is reinstated as Marshal.

Amy, distressed by her husband's refusal to flee, tells him she is leaving on the noon train. In town, Helen Ramírez (Katy Jurado), a Mexican-American businesswoman and former lover of both Kane and Miller, sees the hypocrisy and racism embedded in the townsfolk's behavior and also decides to leave.

As the train whistle signals high noon, Kane finds himself alone, standing against four armed men. In a brilliantly suspenseful showdown, he manages to shoot three of them. When Frank Miller grabs Amy as a hostage, she surprises everyone—including herself—by shooting and killing him to save her husband.

With the town silent and onlookers watching, Kane tosses his badge in the dirt and leaves with Amy, disgusted by the townspeople’s cowardice.

Analysis

Structure and Real-Time Narrative

High Noon is remarkable for its real-time structure—the events unfold almost minute by minute, with frequent shots of clocks ticking down to noon. This creates a tightening sense of tension and dread, mirroring the emotional and psychological pressure Kane endures. The use of time also serves as a metaphor for the inevitability of moral reckoning.

Moral and Ethical Themes

At its heart, High Noon is a morality play—a stark examination of personal integrity, civic responsibility, and courage in the face of overwhelming fear and apathy. Will Kane stands as a symbol of principled resolve. He is not perfect, but he acts because he believes it is right—even when abandoned by those who owe him loyalty.

The film criticizes mob mentality, complacency, and the erosion of communal values. The townspeople represent various rationalizations for inaction: fear, pragmatism, religion, and even petty politics.

Political Allegory

Though set in the Old West, High Noon is deeply rooted in the politics of its time. Screenwriter Carl Foreman wrote it as a thinly veiled allegory of McCarthyism and the Hollywood blacklist. Foreman himself was blacklisted during production for refusing to name names before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Just as Kane is abandoned by his community, many artists and intellectuals were abandoned by their peers during the Red Scare.

Kane's isolation reflects the position of those who stood up to McCarthyist pressure at great personal cost. This subtext gives the film moral weight beyond the Western genre.

Characterization and Performances

- Gary Cooper delivers a quiet but emotionally devastating performance. His portrayal of Kane—aging, vulnerable, determined—won him an Academy Award for Best Actor.

- Grace Kelly, in one of her first major roles, initially appears delicate and idealistic, but her final act of violence complicates her character’s pacifism, suggesting moral convictions can evolve under pressure.

- Katy Jurado, as Helen Ramírez, provides an unusually complex female role for a 1950s Western. She is worldly, wise, and unafraid to confront hypocrisy.

Music and Visual Style

Dimitri Tiomkin’s score, especially the ballad "Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin’", functions as a musical narration and became one of the first film themes to reach popular radio success. It captures the lonesome, fateful mood of the story.

Floyd Crosby’s stark black-and-white cinematography emphasizes the emptiness of the streets and the psychological isolation of the protagonist. Long shadows, high-contrast lighting, and tight framing enhance the sense of foreboding.

Legacy

High Noon is often cited as one of the greatest American films and one of the finest examples of the Western genre. It subverted genre norms by focusing less on action and more on character and conscience. Directors like Stanley Kubrick and Martin Scorsese admired its narrative structure, and it has influenced countless films from 3:10 to Yuma to Die Hard.

President Bill Clinton has called it his favorite movie, using it as a metaphor for political leadership and moral clarity.

Full Cast (Credited):

- Gary Cooper – Marshal Will Kane

- Thomas Mitchell – Mayor Jonas Henderson

- Grace Kelly – Amy Fowler Kane

- Katy Jurado – Helen Ramírez

- Lloyd Bridges – Deputy Marshal Harvey Pell

- Otto Kruger – Judge Percy Mettrick

- Lon Chaney Jr. – Martin Howe (retired marshal)

- Harry Morgan – Sam Fuller

- Ian MacDonald – Frank Miller (outlaw)

- Eve McVeagh – Mildred Fuller

- Morgan Farley – Reverend (church preacher)

- Harry Shannon – Cooper (townsperson)

- Lee Van Cleef – Jack Colby (member of Miller's gang)

- Robert J. Wilke – Jim Pierce (member of Miller's gang)

- Sheb Wooley – Ben Miller (Frank Miller’s brother)

- Ted Stanhope – Station Master

- Tom London – Sam (hotel desk clerk)

- Larry J. Blake – Gillis (bartender)

- William Phillips – Barber

- Virginia Farmer – Mrs. Fletcher

- Jack Elam – Charlie (drunk in jail cell)

- Paul Dubov – Scott (townsperson)

- Dick Elliott – Kibbee

- William Newell – Jimmy (townsperson)

- Cliff Clark – Ed Weaver (townsperson)

- James Millican – Deputy

- Guy Beach – Mr. Fletcher

- Tom Greenway – Ezra (church elder)

Fred Zinnemann's Direction in High Noon: A Study in Moral Tension and Visual Precision

Fred Zinnemann’s direction in High Noon is a masterclass in restraint, clarity, and moral storytelling. Without relying on the typical tropes of Westerns—sweeping landscapes, gunfights for glory, or mythic heroism—Zinnemann crafted a taut, psychological drama about isolation, duty, and the cost of conscience. His choices were precise, almost surgical, lending the film its stark intensity and timeless relevance.

Real-Time Narrative Structure

Zinnemann’s boldest formal decision was to structure the film in near real time. By aligning the film’s pacing with the ticking clock of the town and the approaching train, he turned time itself into a character. The constant recurrence of clock faces—shot from different angles and distances—serves as a drumbeat of inevitability. This real-time construction heightens the suspense but also traps the audience within Kane’s growing isolation.

Zinnemann directs this passage of time with an almost clinical detachment—no stylized editing, no sweeping musical cues to manipulate emotions. Instead, he builds tension slowly, with silent spaces and quiet conversations, trusting the audience to feel the dread accumulating in every minute.

Emphasis on Character Over Action

Zinnemann was never a flashy director. In High Noon, he eschews elaborate camera tricks in favor of human-focused framing. His lens lingers on faces—Gary Cooper’s lined with fatigue and moral resolve, Grace Kelly’s caught in a moment of ideological conflict, Katy Jurado’s reflecting decades of lived experience.

The action scenes are almost anticlimactic by Western standards. The final shootout is swift, grim, and stripped of glamour. Zinnemann deliberately avoids glorifying violence. This choice reinforces his central theme: this isn’t a story about victory, but about responsibility.

Visual Composition and the Psychology of Space

Zinnemann, in collaboration with cinematographer Floyd Crosby, creates a visual world that mirrors the film’s ethical landscape. The wide, sun-bleached streets of Hadleyville feel empty and exposed—an echo of Kane’s emotional abandonment.

Interior shots are often tight, shadowed, and full of silences. Zinnemann uses framing to isolate characters visually long before they’re isolated narratively. He often places Kane off-center or dwarfed by the architecture, visually suggesting the burden he carries and the vacuum of support around him.

He also uses depth of field to show the distance between people in the same room, especially during confrontations—this physical space underlines the moral distance that has grown between Kane and the townspeople.

Direction of Performance

Zinnemann coaxed career-defining performances from his cast, particularly Gary Cooper, who won an Oscar for his portrayal of Kane. Zinnemann allowed Cooper to underplay the role—his quiet demeanor, trembling hands, and anxious glances say far more than dialogue could.

Similarly, Zinnemann gave Katy Jurado one of the first powerful Latina roles in Hollywood, treating her character Helen Ramírez with a respect rarely seen in 1950s Westerns. Under his direction, her scenes are layered with unspoken history and social commentary.

Even the townspeople, often with only a few lines each, are directed to express entire moral arguments with their posture, tone, or silence. Zinnemann turns the town into a chorus of conscience, each citizen reflecting different shades of fear and complicity.

Political Subtext and Directorial Courage

Though Zinnemann did not write the script, he fully embraced its political allegory. During the height of McCarthyism, when many filmmakers shied away from controversy, Zinnemann directed High Noon as a clear-eyed examination of courage under pressure. The fact that screenwriter Carl Foreman was blacklisted during production only reinforced the film’s thematic weight.

Zinnemann’s direction never moralizes overtly. Instead, he uses cinema as quiet confrontation, forcing the viewer to reflect on their own values: Would you stand with Kane? Would you stay silent? Would you look away?

Subversion of the Western Genre

Fred Zinnemann was not a Western director by tradition—and that’s part of what made High Noon so distinctive. He subverted nearly every expectation of the genre:

- The lone hero is not triumphant, but abandoned.

- The town is not a source of community, but of fear.

- The violence is not climactic, but necessary and grim.

- The departure at the end is not heroic, but disillusioned.

Zinnemann turned the Western inward—into a moral battleground rather than a physical one. In doing so, he redefined what a Western could be.

Conclusion

Fred Zinnemann’s direction in High Noon is marked by elegance, economy, and ethical gravity. Every shot, every pause, every framing choice serves the story’s core concern: the burden of doing what’s right when no one else will.

He didn’t just direct a suspenseful film—he orchestrated a cinematic parable, one that continues to resonate in any era where principles are tested and silence can be a betrayal. High Noon remains not just a film, but a question—and Zinnemann makes sure we, like Kane, must answer it for ourselves.

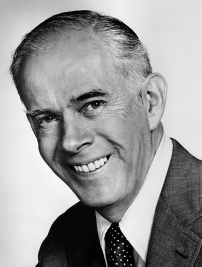

Gary Cooper in High Noon: A Study in Stoic Vulnerability

Gary Cooper’s portrayal of Marshal Will Kane is a performance of subtlety, control, and emotional resonance. At a time when Western heroes were often loud, brash, and physically dominant, Cooper redefined what cinematic bravery could look like. His Kane is not a swaggering gunslinger, but a weary, aging man burdened by duty and betrayed by his community. His performance is not only the emotional anchor of the film—it is the film.

Understatement as Power

Cooper's acting in High Noon is marked by economy of expression. He rarely raises his voice. His movements are measured. His face—lined, sun-drenched, often shadowed—speaks volumes without words. Rather than grand declarations, Cooper gives the audience flickers of uncertainty: a hand that trembles slightly as he loads his gun, a hesitant glance down a lonely street, a jaw clenched in quiet anger.

This restraint doesn’t make Kane weak—it makes him human. In an era when heroism was often equated with loud confidence, Cooper shows us quiet resolve as the highest form of courage.

Physical Performance and Aging Heroism

At 51, Cooper was older than most Western leads at the time, and Zinnemann and Cooper lean into that. Kane walks with a slight stiffness. His face shows age and exhaustion. Rather than masking these traits, Cooper uses them to enhance the character’s internal struggle: this is a man who shouldn’t have to fight anymore, who has earned his peace, but is forced to sacrifice it because others won’t do their part.

His physical performance is especially powerful in moments of solitude. The way he looks at the badge before pinning it back on. The way he stands alone on empty streets, his long shadow stretching behind him. His Kane is not invincible—he's worn down, but stands up anyway.

Emotional Nuance and Internal Conflict

Cooper’s face becomes a battleground of emotions: fear, frustration, betrayal, sorrow. His eyes frequently flicker with doubt, especially as one ally after another turns him away. But behind that doubt is something stronger: a moral clarity that gives him no choice but to stay.

One of the most striking aspects of Cooper’s performance is that he makes silence feel heavy. In scenes where others speak, he often listens quietly, his reactions more important than their words. His silences are filled with weight—he’s absorbing not only what is said, but what it means for his own choices.

Even when pleading with others to help, there is no self-pity in his voice. Only urgency. Only truth.

Chemistry with Other Characters

- With Grace Kelly (Amy), Cooper creates a heartbreaking contrast between newlywed tenderness and ideological divide. In their few quiet moments together, his gentleness underscores what’s at stake.

- With Katy Jurado (Helen Ramírez), there’s tension laced with unspoken history. He treats her with respect, and their scenes are charged with emotional maturity.

- With the townspeople, Cooper’s performance grows more brittle as the betrayals pile up. Each rejection is met not with rage, but with increasing isolation—a man growing smaller in the face of collective cowardice.

The Final Scene: A Performance Without Words

Perhaps the most iconic moment of Cooper’s performance comes at the very end. After defeating Frank Miller and saving the town, Kane steps into the silent street. He looks at the townspeople who had abandoned him, then slowly removes his badge and drops it in the dirt.

He says nothing. But in that gesture—and the tired look on his face—we feel everything: disillusionment, moral exhaustion, and the final cost of standing alone.

Few actors could deliver such a climax with only body language. Cooper does so with devastating simplicity.

Conclusion

Gary Cooper’s performance in High Noon is a study in stoic vulnerability. He gives us a hero who bleeds, who doubts, who ages—but who still stands firm when it matters most. His work doesn’t demand applause; it demands reflection.

This role earned him the Academy Award for Best Actor, but its true legacy lies in how it redefined the Western hero—not as an invincible gunslinger, but as a man who does the right thing even when it costs him everything.

Memorable Quotes from High Noon:

- “I’ve got to, that’s the whole thing.”

— Will Kane

Said to Amy when she pleads with him to leave town. This line captures the moral compulsion Kane feels, even when he knows he stands alone. - “People gotta talk themselves into law and order before they do anything about it. Maybe because down deep they don’t care.”

— Helen Ramírez

A sharp commentary on the cowardice and complacency of the townspeople, delivered by one of the most clear-eyed characters in the film. - “You're asking me to wait an hour to find out if I’ll be a widow. That’s not fair.”

— Amy Fowler Kane

Amy expresses her deep conflict between her pacifist beliefs and her love for her husband, who insists on staying to face Miller. - “It’s too late to start quarreling now, Will. In less than an hour, Frank Miller will be here.”

— Harvey Pell

This line underscores the urgency of the situation, even as petty disagreements and self-interest continue to surface. - “I don’t care who’s right or who’s wrong. There’s gonna be trouble, and I don’t want any part of it.”

— Churchgoer

A line that exemplifies the town’s broader attitude—moral neutrality used as a shield against personal risk. - “This is just a dirty little village in the middle of nowhere. Nothing that happens here is really important.”

— Helen Ramírez

A cynical but piercing observation about how people often rationalize inaction—by minimizing the importance of place and principle. - “I sent a man up five years ago for murder. He’s back today. I expect he’s looking for me.”

— Will Kane

A quiet, understated line early in the film that sets the stakes with chilling simplicity. - “You’re a good-looking boy, you’ve got big, broad shoulders. But he’s got money and he’s got power.”

— Helen Ramírez to Harvey Pell

A moment of brutal honesty from Helen to her former lover, showing her clarity and disillusionment with romantic and social power dynamics. - “You didn’t see anything. You were never here.”

— Will Kane to a hotel clerk

Spoken after trying to rally support and facing more cowardice—this line is loaded with bitterness and resignation. - “So that's the kind of man you are.”

— Amy Fowler Kane, after Will chooses to stay and face danger rather than flee with her.

Initially meant with disapproval, it becomes more poignant by the end when she understands his principles—and acts on them herself. - (No words – just the sound of the badge hitting the dirt)

— Final gesture by Will Kane

Perhaps the most powerful “quote” is not spoken at all. When Kane throws his badge to the ground after the townspeople emerge, it’s a wordless condemnation of their cowardice.

Classic Scenes from High Noon

The Wedding Scene (Opening Sequence)

Setting: A quiet Quaker wedding between Will Kane and Amy Fowler.

Why it matters:

The film opens with a false sense of peace. The sun is shining, the ceremony is modest, and Kane is hanging up his badge. This serenity is immediately shattered by the news that Frank Miller has been released and is on his way back. The scene sets the stage for Kane’s inner conflict: peace vs. duty, love vs. justice.

It's a symbolic beginning—the Marshal’s transition into a new life is aborted the moment the past rides back into town.

The Clock Montage (Throughout the Film)

Setting: Shots of clocks ticking down to noon appear repeatedly.

Why it matters:

This is one of the most iconic formal devices in film history. Fred Zinnemann and editor Elmo Williams intercut scenes of Kane’s efforts with tight close-ups of clocks, emphasizing the relentless forward march of time.

The real-time structure becomes a visual and psychological drumbeat, heightening suspense and underlining the inescapability of confrontation.

Kane Pleads for Help at the Church

Setting: Kane interrupts a church service to ask for deputies.

Why it matters:

This is a turning point in the film’s moral core. The townspeople debate whether to help or remain neutral. Arguments range from “we owe him” to “this isn’t our fight” to “he’s bringing trouble on himself.”

Zinnemann stages it like a town hall—a microcosm of public ethics and civic decay. Kane’s vulnerability here is painful to watch, and the scene ends with the congregation doing… nothing.

Helen Ramírez and Amy’s Conversation

Setting: Two women from different worlds talk in Helen’s hotel room.

Why it matters:

This quiet scene between Katy Jurado and Grace Kelly breaks genre norms. It’s rare in Westerns (especially at the time) for two female characters to talk—let alone about morality, men, and survival.

Helen, worldly and realistic, contrasts sharply with Amy’s idealism. Their exchange gives depth to both characters and raises questions about what kind of courage the town truly needs.

The Empty Streets

Setting: Kane walks through the town alone, looking for support.

Why it matters:

In a series of long, static shots, we see Kane walking through eerily empty streets. Storefronts close. Curtains are pulled shut. No one stands with him.

These silent, suspenseful sequences symbolize communal abandonment. Zinnemann uses space to isolate Kane, and Cooper’s body language—rigid, determined, weary—does the rest.

The Final Shootout

Setting: The noon train arrives. Miller and his gang confront Kane.

Why it matters:

Despite the buildup, the shootout is short, harsh, and unromantic. Kane picks off Miller’s men one by one in alleys and behind buildings—not with flair, but with grit and desperation. When Amy kills a man to save him, it completes her arc from pacifism to moral engagement.

This sequence is less about victory than survival, and the emotional cost of doing the right thing alone.

Kane Throws Away His Badge (The Final Scene)

Setting: After the showdown, townspeople emerge. Kane throws his badge to the dirt.

Why it matters:

It’s the most powerful scene in the film, delivered without words. The townspeople come out too late—after the danger has passed. Kane, disgusted, looks at them, drops his badge, and walks away with Amy.

It’s a moment of moral judgment. No speech, no forgiveness—just silence and a gesture. It's an indictment of cowardice and complicity.

Awards and Recognition

Academy Awards (Oscars) – 1953

Wins (4):

- Best Actor in a Leading Role – Gary Cooper

- Best Film Editing – Elmo Williams and Harry W. Gerstad

- Best Music, Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture – Dimitri Tiomkin

- Best Music, Original Song – "Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin’" (Music by Dimitri Tiomkin, Lyrics by Ned Washington)

Nominations (3):

- Best Picture – Stanley Kramer (Producer)

- Best Director – Fred Zinnemann

- Best Writing, Screenplay – Carl Foreman

Golden Globe Awards – 1953

Wins (4):

- Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama – Gary Cooper

- Best Supporting Actress – Katy Jurado

- Best Score – Dimitri Tiomkin

- Henrietta Award (World Film Favorite – Male) – Gary Cooper

BAFTA Awards (British Academy Film Awards) – 1953

Nominations (2):

- Best Film from Any Source

- Best Foreign Actor – Gary Cooper

Directors Guild of America Awards – 1953

- Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures – Fred Zinnemann (Nominated)

Writers Guild of America Awards – 1953

- Best Written American Drama – Carl Foreman (Nominated)

National Board of Review – 1952

- Top Ten Films of the Year – High Noon (Included)

Other Honors:

- Preserved in the U.S. National Film Registry – Selected by the Library of Congress in 1989 for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

- AFI (American Film Institute) Rankings:

- #27 on AFI’s 100 Years... 100 Movies (original 1998 list)

- #33 on AFI’s 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)

- #2 on AFI’s 10 Top 10 Westerns

- #20 on AFI’s 100 Years... 100 Heroes & Villains (Will Kane as hero)

- #75 on AFI’s 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes ("Do not forsake me, oh my darlin’...")