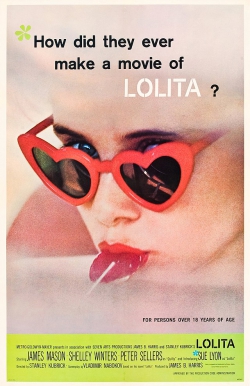

Lolita - 1962

back| Released by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

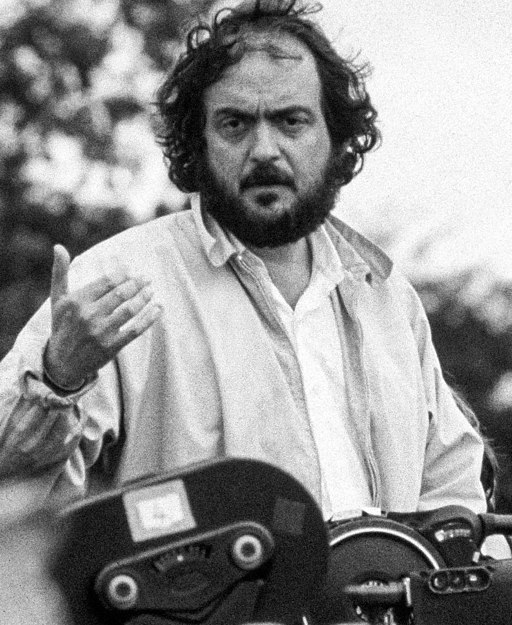

| Director | Stanley Kubrick |

| Producer | James B. Harris |

| Script | Screenplay by Vladimir Nabokov (based on his 1955 novel Lolita) - Note: Kubrick and Harris significantly altered the screenplay from Nabokov’s original draft |

| Cinematography | Oswald Morris |

| Music by | Nelson Riddle |

| Running time | 152 minutes |

| Film budget | $2 million |

| Box office sales | $9.25 million |

| Main cast | Sue Lyon - James Mason - Shelley Winters - Peter Sellers |

Lolita

A Haunting Tale of Obsession and Corrupted Innocence

Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita (1962) is a darkly satirical adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial novel, following Professor Humbert Humbert, who becomes infatuated with his landlady’s teenage daughter, Lolita. Told through Humbert’s distorted perspective, the film explores obsession, manipulation, and the corruption of innocence, while cleverly navigating censorship through implication and irony. Sue Lyon delivers a haunting performance as Lolita, embodying youthful complexity and emotional ambiguity. Kubrick’s restrained direction and Peter Sellers’ surreal turn as Clare Quilty add layers of tension and dark comedy.

Though critically praised, the film sparked controversy for its subject matter and was limited in awards recognition. Over time, Lolita has gained recognition as a bold, psychologically complex work that critiques male delusion and cultural hypocrisy. It remains a key early entry in Kubrick’s career, notable for its stylistic control and unsettling emotional undercurrents.

Related

Lolita – 1962

Analysis of the Movie

Kubrick structures Lolita as a psychological drama wrapped in layers of irony and dread. The film begins in medias res, with Humbert Humbert committing a murder. From this disorienting opening, the rest of the film unfolds as a reflective confession — a visual memoir shaped by regret, obsession, and emotional decay.

We are then taken back in time to the arrival of Humbert, a suave, European professor who settles in a New England town. Seeking lodging, he visits the home of Charlotte Haze, a widow whose desperation for male companionship is palpable. Her home is garish and socially aspirational, filled with feminine clutter — a reflection of Charlotte’s fragile identity.

Humbert’s disinterest in Charlotte vanishes when he first sees her daughter: Dolores Haze, lounging in the garden, licking an ice cream cone — a symbol of innocence turned into something disquieting through Humbert’s gaze. He is instantly infatuated. From this moment, Lolita becomes a film about perception: how reality is warped by desire, control, and memory.

Humbert marries Charlotte not out of love, but to remain near Lolita. Charlotte, unaware of his true motives, begins to feel secure in her role as wife and mother. This false domesticity is shattered when she discovers Humbert’s diary — a literal and metaphorical unveiling of the horror she’s unknowingly enabled. Distraught, she runs into traffic and is killed.

This sudden event transforms Humbert from secret voyeur to manipulative guardian. He retrieves Lolita from summer camp and tells her nothing of her mother’s death until later, gently revealing it with an eerie calm. The two begin traveling, staying in motels, with Humbert gradually seducing her under the guise of fatherly affection. The film tiptoes around the sexual elements, but the implications are clear: Lolita is under psychological and emotional duress.

As they travel, the presence of Clare Quilty, a mysterious playwright, becomes more frequent. He lurks in the background, often disguised, watching them. Quilty is both a comic figure and a grotesque specter, adding a surreal quality to the story.

Over time, Lolita grows increasingly defiant. Humbert becomes possessive, paranoid, and volatile. Eventually, she runs away — supposedly to stay with an aunt, but in truth to escape Humbert's grasp. She disappears from his life.

Years later, Humbert receives a letter from Lolita. She is now pregnant, married, and poor. He visits her, hoping to rekindle their relationship. But Lolita, emotionally scarred yet composed, refuses. She accepts money, but not love.

Humbert then seeks out and kills Clare Quilty, who had seduced and exploited Lolita during her time away. The film ends with Humbert in prison, awaiting trial — an epilogue reveals he dies of a heart attack shortly after.

Character Analysis

Humbert Humbert

At once charismatic and monstrous, Humbert is a man whose intelligence and charm conceal a hollowed soul. Kubrick presents him not as a typical villain but as a case study in rationalized immorality. His narration is eloquent, even poetic, which disturbs more than it disarms. He never truly understands Lolita — he only sees her through his self-serving fantasy.

Dolores “Lolita” Haze

Lolita is perhaps the film’s most misunderstood character. While playful, sarcastic, and spirited, she is also deeply vulnerable. Kubrick and Sue Lyon (only 14 during filming) craft a performance that suggests layers beyond her age — not sexual maturity, but emotional complexity. Lolita is not complicit; she is surviving. She has moments of rebellion, laughter, and even manipulation, but always within the confines of a power structure she cannot control.

Charlotte Haze

Charlotte is a portrait of desperate respectability. She is often mocked by the film's tone — loud, insecure, tasteless — yet her fate is ultimately tragic. She is a woman caught in a social game she doesn’t fully understand, unaware of the danger she has invited into her home.

Clare Quilty

Peter Sellers plays Quilty as a bizarre, fragmented persona — a playwright, a pervert, a madman, a mirror. His role is ambiguous: a shadow to Humbert, a warning, a rival. Quilty embodies a more chaotic version of Humbert’s pathology. Where Humbert intellectualizes, Quilty improvises. His death is the only moment Humbert fully relinquishes control — not to justice, but to rage.

Visual and Stylistic Analysis

Kubrick’s direction in Lolita is restrained and calculated:

- Black-and-white cinematography by Oswald Morris adds a stark, almost documentary-like atmosphere. It evokes a sense of timelessness and emotional coldness. This choice removes the luridness that color might have imposed and adds a veneer of respectability over the disturbing content.

- Framing and composition reinforce Humbert’s psychology. Lolita is often viewed from a distance or in fragmented reflections — never whole, never on her own terms.

- Symbolic motifs (sunglasses, lollipops, motel keys, swings) recur as metaphors for surveillance, secrecy, and corrupted innocence.

- Music by Nelson Riddle subtly contrasts scenes. Light, romantic melodies underscore deeply unsettling moments, heightening the irony and tension.

Themes and Interpretation

Obsession and the Male Gaze

Humbert's obsession is not rooted in love, but in control and idealization. He transforms Lolita into a projection, not a person. The film critiques how desire can dehumanize, and how easily that can be masked by cultural intellect or sentimentality.

American Conformity and Hypocrisy

The suburban setting, motels, and "wholesome" backdrop are deliberate. Kubrick satirizes 1950s America as a place that hides depravity behind manners, curtains, and Coca-Cola. Humbert is an outsider, but the society he enters is complicit through its silence.

Power, Innocence, and Corruption

The film constantly asks: who holds power? Lolita, though seemingly flirtatious and independent, is shaped by trauma. Her rebellion is not agency, but resistance. Humbert’s power is not just physical, but cultural — a man with education, status, and language.

Duality and Mirrors

Quilty is Humbert’s doppelgänger, but also his undoing. Their confrontation is theatrical and surreal — Humbert must destroy the version of himself he refuses to see. Yet in killing Quilty, he doesn't redeem himself; he only completes the arc of destruction.

Conclusion: A Disturbing Elegy

Kubrick’s Lolita is not about romance, nor about scandal. It is a study in delusion, decay, and the lies we tell ourselves. It implicates not only its characters but the viewer — asking us to confront the ease with which charm, wit, and art can obscure moral collapse.

While restrained by the censorship of its time, Lolita is more unsettling because of what it doesn’t show. It lingers in suggestion, implication, and irony. Kubrick transforms Nabokov’s provocative novel into a cinematic riddle — a black comedy that is anything but funny, a love story with no love, a tragedy with no redemption.

Main Cast

- James Mason – Professor Humbert Humbert

- Sue Lyon – Dolores "Lolita" Haze

- Shelley Winters – Charlotte Haze

- Peter Sellers – Clare Quilty

Supporting Cast

- Gary Cockrell – Richard T. "Dick" Schiller (Lolita’s eventual husband)

- Jerry Stovin – John Farlow (Humbert’s colleague and friend)

- Diana Decker – Jean Farlow (John’s wife)

- Lois Maxwell – Miss Fromkiss (schoolteacher at Beardsley School)

- Cec Linder – Dr. Keegee (Humbert’s colleague)

- Marianne Stone – Vivian Darkbloom (an anagram of Vladimir Nabokov, Quilty’s female companion)

- Marion Mathie – Miss Pratt (Headmistress at Beardsley School)

- James Dyrenforth – Dr. Melin (Beardsley School physician)

- John Harrison – Reverend Rigger

- Maxine Holden – Beardsley Girl

- Sue Lloyd – Young Nurse (uncredited)

- Tania Mallet – Girl at Christmas Party (uncredited)

Classic Trailer Lolita 1962

Direction Analysis of Lolita (1962) – Stanley Kubrick

A Masterclass in Tone Management

Kubrick walks a razor-thin line in Lolita, balancing dark comedy, satire, psychological drama, and moral horror — all while being constrained by the censorship rules of early 1960s American cinema (the Hays Code).

Rather than confront the controversial subject matter directly, Kubrick veils it in irony, distancing the audience from what could have been sensationalized or lurid. The viewer is constantly suspended between laughter and discomfort — unsure whether to smirk or recoil. This uneasy ambiguity is intentional and meticulously maintained through his direction.

Example: Quilty’s murder scene at the start (and end) is surreal and almost slapstick — but the underlying tension makes it grotesque rather than comic. This interplay is Kubrick’s hallmark: discomfort disguised as humor.

Visual Restraint and Suggestion over Explicitness

Due to the strict censorship standards of the time, Kubrick couldn’t portray sexual content or overt child-adult intimacy. Instead of fighting this, he transformed the limitation into an artistic advantage. His direction leans heavily on subtext, innuendo, facial expressions, silence, and suggestion.

Kubrick deliberately avoids showing physical acts — instead, he crafts long, tense scenes in confined spaces (motels, cars, bedrooms) where psychology, not action, takes center stage. The audience feels the pressure and the implications without ever being shown “too much.”

Example: The breakfast scene where Lolita playfully touches Humbert’s hand under the table, while Charlotte prattles on, is layered with suppressed desire, dread, and irony — filmed almost entirely in medium shots and reaction cuts.

Precision Framing and Symmetry

Even in his early black-and-white work, Kubrick’s eye for compositional control is evident. Scenes are often framed with mathematical precision. The characters are carefully placed in space, not just for aesthetics but to reflect power dynamics and psychological tension.

- Humbert is frequently shown isolated, either physically (framed alone in doorways or reflections) or emotionally (surrounded by others but emotionally detached).

- Lolita, on the other hand, is often seen in fragmented ways — behind curtains, in profile, through windows or mirrors — emphasizing Humbert’s distorted, incomplete perception of her.

Irony Through Mise-en-Scène

Kubrick loads the visual environment with ironic contrasts:

- Bright, clean suburban homes frame dark, disturbed relationships.

- Innocent objects like sunglasses, lollipops, and stuffed animals become loaded symbols of corruption and desire.

- Overly cheerful music plays over disturbing scenes, forcing the audience to confront the emotional dissonance.

Example: The motif of sunglasses (especially when worn by Lolita) becomes a barrier — a shield, a symbol of manipulation, and a mask. They protect her eyes and obscure her feelings, just as the film’s surface style hides its disturbing core.

Sound and Silence

Kubrick uses silence strategically — to isolate characters, stretch tension, or underscore emotional absence. Dialogue is often sparse during pivotal moments. When he uses sound, it’s usually for contrast or irony.

- Nelson Riddle’s score adds a dreamy, almost romantic overlay to a story that is morally nightmarish. The music doesn’t guide us toward empathy — it undercuts it, creating emotional confusion.

- Peter Sellers’ improvisations as Quilty are given space to breathe — Kubrick lets him ramble and dominate scenes, turning dialogue into surreal performance. These long takes shift the film into absurdism, making Quilty a strange, haunting figure of unmoored identity.

Control of Performance

Kubrick’s direction of actors in Lolita shows his early tendency toward total control, tempered here by collaboration:

- James Mason gives a performance full of restraint and internal pressure. Kubrick draws out a character who is aware of his depravity but refuses to name it. Humbert is all self-justification and quiet desperation.

- Sue Lyon, only 14, is directed not to be overtly sexualized, but to evoke confidence tinged with confusion. Her Lolita is bratty, coy, witty — but not complicit. Kubrick avoids making her an object of desire; instead, he makes us uncomfortable with the fact that Humbert sees her that way.

- Peter Sellers is Kubrick’s wildcard. He’s allowed improvisational space that blurs reality. His presence grows more menacing the more absurd he becomes, which is precisely Kubrick’s thematic point: madness doesn’t always look like a monster — sometimes, it wears a smile and a bathrobe.

Narrative Structure and Temporal Disruption

Kubrick opens the film with the ending — Quilty’s death — and then backtracks. This isn’t just a storytelling gimmick; it immediately removes suspense and replaces it with dread. From the first moment, we know Humbert is a killer. The rest of the film isn’t about what happens, but how and why — a psychological autopsy, not a mystery.

This narrative choice also distances the viewer from Humbert’s self-mythologizing. His voiceover becomes suspect, unreliable — we already know how it ends.

Conclusion: A Film of Suppressed Fire

Kubrick’s direction in Lolita is a model of restraint and implication. He does not tell us what to feel. Instead, he disorients, teases, and implicates the viewer, turning us into reluctant witnesses of moral collapse.

He doesn’t make Humbert charismatic — he makes him believe he is. He doesn’t make Lolita seductive — he shows how easily others project seduction onto her. And he doesn’t make the film shocking through visuals — he makes it haunting through suggestion.

It is this deliberate tension — between surface politeness and buried horror, between social comedy and emotional tragedy — that defines Lolita as one of Kubrick’s most quietly disturbing and masterfully directed films.

Sue Lyon as Lolita

Balancing Innocence and Defiance

Sue Lyon was only 14 years old when cast in the role of Lolita, and that fact alone adds layers of discomfort and realism to the character. Lyon’s performance is remarkable in how it avoids the traps that the role could easily fall into. Rather than playing Lolita as either a helpless victim or a manipulative seductress — both of which would flatten her — Lyon strikes a delicate balance between naiveté and precociousness.

Her Lolita is a real teenager: moody, sarcastic, flirtatious, emotionally impulsive. She chews gum loudly. She slouches. She plays with her hair. She rolls her eyes at her mother. These are not just affectations — they form a naturalistic portrait of a young girl who is navigating adolescence, not wielding it as a weapon.

Key Scene Example: In the garden scene when Humbert first sees her, she’s lying in the sun, licking an ice cream cone, in a swimsuit. It’s not what she is doing that’s provocative — it’s how Humbert (and the camera via his gaze) interprets it. Lyon performs the moment with complete casualness, adding to the discomfort — because we realize the problem lies not with her, but with the adult perception of her.

The Weaponization of Teen Spirit

Throughout the film, Lyon plays Lolita as someone who is half-aware of the power she holds over Humbert — but never in control of it. She teases, flirts, and mocks him. But she’s not orchestrating anything. Rather, she’s trying to understand her own role in this strange, claustrophobic relationship.

There’s a volatility to Lyon’s performance that captures the turbulence of teenage identity: one moment coquettish, the next cold and withholding, then suddenly warm and childlike. These shifts feel authentic, not calculated.

Example: In the motel scenes, Lyon is playful, lying on the bed, making jokes. But then she turns away or becomes emotionally distant. Kubrick often films her with her back to Humbert — reinforcing that she’s there physically, but emotionally removed.

Emotional Shielding and Quiet Pain

Much of Lyon’s performance is defined by what she holds back. Kubrick doesn’t allow her long monologues or dramatic breakdowns — instead, we see her inner life in fragments, through small behavioral details:

- The way she abruptly stops smiling when no one laughs at her joke.

- The silence in her eyes when Humbert tries to buy her affection.

- The forced cheerfulness in the later scenes when she’s poor, pregnant, and resigned to her fate.

Her final scene with Humbert is devastating in its restraint. Lyon plays Lolita as someone who has aged emotionally far beyond her years. She’s not a tragic heroine — she’s a survivor. There’s bitterness in her voice, but also fatigue. She no longer fights; she simply endures.

Example: When Humbert offers to take her away again, and she refuses, she doesn’t cry. Instead, Lyon lets the pain sit in her eyes and voice. Her maturity in that moment — quietly rejecting the man who once controlled her — is one of the most powerful moments in the film.

Physicality and Body Language

Lyon’s performance is not just verbal — it’s deeply physical. She uses posture, eye contact, and movement to reflect the evolution of Lolita’s emotional state:

- In early scenes, she lounges with the confidence of a girl who knows she’s being watched — not sexually, but socially.

- During their travels, she becomes more restless and irritable. She slouches in the car, fiddles with her fingers, slams doors.

- In later scenes, especially when she’s pregnant, her energy is subdued. Her body becomes less expressive — not because she’s older, but because she’s worn down.

Kubrick often films her from angles that emphasize her distance — she’s frequently shown through glass, in mirrors, or from behind. This distancing is enhanced by Lyon’s subtle use of physical space: she’s rarely comfortable near Humbert, and often moves just out of reach.

The Mask of Normalcy

One of the most haunting aspects of Lyon’s performance is her ability to make Lolita appear almost normal — even in the midst of exploitation and control. She laughs. She makes jokes. She gossips. This surface normalcy is not a flaw in the performance — it’s the point.

Kubrick uses this to show how easily trauma and manipulation can be masked by everyday behavior. Lyon portrays Lolita not as someone visibly falling apart, but as someone who has to pretend everything is fine — because no one is really looking closely enough to see the truth.

A Star Born into Controversy

Sue Lyon’s performance was widely praised at the time and won her a Golden Globe for Most Promising Newcomer – Female. However, her casting and subsequent fame were also marked by controversy and public scrutiny, much like the character she played. In retrospect, her performance is not only brave — it’s tragically layered, as Lyon herself was thrust into a kind of symbolic role in the public imagination.

Yet what endures is the fact that she brought empathy, complexity, and emotional truth to a role that could have been reduced to provocation or stereotype.

Conclusion: A Performance of Quiet Devastation

Sue Lyon’s portrayal of Lolita is remarkable not because she is seductive or shocking — but because she is real. She gives us a portrait of a young girl trying to remain herself in a world that refuses to see her clearly. Through every shrug, smirk, and silence, Lyon reveals a character who is at once vulnerable, clever, stubborn, and profoundly wounded.

Under Kubrick’s watchful, ironic direction, Lyon turns Lolita from a literary symbol into a human being — and in doing so, delivers one of the most quietly heartbreaking performances of 1960s cinema.

Sue Lyon's Lolita (1962) vs. Dominique Swain’s performance in Adrian Lyne’s Lolita (1997)

Age and Appearance: A Key Difference in Casting

- Sue Lyon (1962): 14 during filming, but made to look older. With heavy makeup, big hair, and glamorous costumes, she often appears closer to 17–18. This was partly due to censorship concerns — Kubrick needed to soften the impact of the sexual implications.

- Dominique Swain (1997): 15 during filming and portrayed as such. Lyne intentionally emphasized her youth, emotional vulnerability, and adolescent awkwardness. Swain looks and behaves much more like a real teenage girl — braces, flat hair, oversized clothes, uneven posture. This gives her version of Lolita a rawer, more uncomfortable authenticity.

Takeaway: Lyon’s Lolita is stylized, iconic, and enigmatic. Swain’s Lolita is more naturalistic, fragile, and childlike — which makes the story feel darker and more tragic.

Characterization and Emotional Access

- Sue Lyon: Plays Lolita with ambiguity and irony. Her Lolita is flippant, sarcastic, emotionally guarded. Kubrick keeps her inner life at a distance, partly because the story is told through Humbert’s unreliable lens. Lyon’s performance reflects this — she seems like someone we never fully understand, which supports Kubrick’s theme of male delusion and projection.

- Dominique Swain: Gives a performance that’s emotionally transparent and reactive. Her Lolita laughs, cries, begs, throws tantrums — and the film lingers on these emotions. Lyne gives her more scenes that show pain, confusion, and trauma. This reclaims the character’s humanity and shifts audience sympathy much more clearly to her.

Takeaway: Lyon’s Lolita is shaped by suggestion. Swain’s Lolita is shaped by exposure. One is observed, the other is seen.

Style of Performance

- Lyon: Understated, restrained, emotionally internal. Her performance thrives on small gestures — a sarcastic grin, a turned back, a sudden silence. Lyon often plays against the moment, avoiding melodrama.

- Swain: More expressive, reactive, and emotionally open. She conveys Lolita’s youth through emotional volatility — she’s defiant one moment, sobbing the next. This mirrors the emotional chaos of a teenager under immense psychological pressure.

Takeaway: Lyon’s strength is in her quiet control; Swain’s in her emotional transparency. Both are powerful in different ways.

Relationship with Humbert

- With James Mason (1962): The dynamic is tense, but stylized. Humbert maintains a kind of theatrical charm. Lolita pushes back, but much is left unsaid. The film uses irony and suggestion to show power imbalances.

- With Jeremy Irons (1997): The relationship is far more explicit and emotionally violent. Irons’ Humbert is romanticized in voice-over but shown on screen to be manipulative and predatory. Swain’s Lolita is visibly worn down by the relationship. There’s less “chemistry” and more emotional damage.

Takeaway: The 1962 version keeps the relationship cloaked in ambiguity and wit. The 1997 version lays it bare — uncomfortable, invasive, and deeply sad.

Cultural Context and Directorial Framing

- Kubrick/Lyon (1962): Had to work within censorship, which led to subtlety and irony. Kubrick directed Lyon to be provocative but emotionally unreadable. The result is a film that critiques male obsession more than it explores the girl at its center.

- Lyne/Swain (1997): Faced no such restrictions. Lyne intentionally gave Lolita agency, vulnerability, and voice. Swain is given close-ups, breakdowns, and scenes that explore her inner world. Lyne’s Lolita is a person, not a symbol.

Takeaway: The 1962 version is about Humbert’s illusion of Lolita. The 1997 version tries to recover who Lolita really is — and what she endured.

Key Quotes from Lolita (1962)

Humbert Humbert (voice-over):

"She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms, she was always... Lolita."

- This is the film’s most famous line — adapted directly from Nabokov’s novel. It’s poetic, obsessive, and haunting. It defines Humbert’s romanticized fixation and the transformation of Dolores Haze into the mythical “Lolita” in his mind.

Humbert Humbert (voice-over):

"What I had madly possessed was not she, but my own creation, another, fanciful Lolita... perhaps more real than Lolita herself."

- A rare moment of clarity, this line hints at Humbert’s realization that his love was not for a real person, but for an imagined fantasy — making his obsession even more delusional.

Humbert Humbert (to Lolita):

"I’m not a monster. You mustn’t think I’m a monster."

- Spoken during a tense scene, this line underscores Humbert’s self-denial and his desperate need for moral justification. It’s chilling because it reveals how far gone he is — trying to frame himself as sympathetic while controlling her life.

Clare Quilty (to Humbert, before being killed):

"You think I'm sort of a sinister character... with designs on young girls?"

- Quilty’s sarcastic tone and evasive wordplay make this line unsettling. He mirrors Humbert in many ways, and this moment serves as a twisted reflection of Humbert’s own hidden motives.

Lolita (to Humbert):

"You mean we’re going to sleep in the same room?"

- This line is spoken early in their road trip and is seemingly innocent, yet laced with subtext. It highlights the inappropriate nature of their arrangement and hints at the emotional confusion Lolita experiences.

Charlotte Haze (to Humbert):

"You’re the only man I’ve ever met who didn’t just want to use me."

- This line is tragically ironic. Charlotte believes she’s found genuine affection in Humbert, when in reality he despises her and is only using her to get close to her daughter.

Humbert Humbert (voice-over):

"Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul."

- Though not delivered exactly as in the novel, this iconic line is echoed in the film’s tone and internal monologue. It’s literary, lyrical, and deeply unsettling — embodying the central conflict of beauty laced with horror.

Classic Scenes from Lolita (1962)

The Opening Scene – The Murder of Clare Quilty

Scene:

The film begins with Humbert Humbert entering a decrepit mansion in the early morning and confronting the disheveled, drunken Clare Quilty. What unfolds is a surreal, tension-filled confrontation laced with sarcasm and wordplay, which ends with Humbert shooting Quilty multiple times.

Why It’s Classic:

- The opening with the ending sets the tone for the entire film — cold, ironic, and morally ambiguous.

- Peter Sellers gives a bizarre, improvisational performance that turns the murder into a grim farce.

- It immediately inverts expectations: the supposed hero kills a man, and we’re left to unravel why.

Themes:

- Madness and obsession

- Surrealism and irony

- The destructive end of unchecked desire

The Garden Introduction – Humbert Sees Lolita for the First Time

Scene:

Humbert arrives at Charlotte Haze’s house to inspect a room for rent. As he sits in the garden, he notices Lolita for the first time — lying in the sun, wearing sunglasses and a bathing suit, licking an ice cream cone.

Why It’s Classic:

- This is the film’s visual introduction of Lolita as the object of desire — from Humbert’s perspective.

- Kubrick frames the scene in a way that mixes mundane suburban normalcy with erotic suggestion — but the discomfort is in the gaze, not the act.

- The moment is understated yet deeply unsettling, and it defines the power dynamic that drives the rest of the film.

Themes:

- The male gaze and projection

- Corruption of innocence

- Illusion versus reality

Charlotte Reads the Diary

Scene:

After marrying Humbert, Charlotte discovers his secret diary — in which he writes about his hatred for her and his obsession with Lolita. She reads it aloud, horrified, and storms out of the house before being hit by a car and killed off-screen.

Why It’s Classic:

- Shelley Winters gives a raw, desperate performance — tragic, not just ridiculous.

- The scene marks a turning point in the film’s morality and structure: with Charlotte gone, Humbert becomes Lolita’s sole guardian.

- The diary is symbolic — a mirror into Humbert’s mind and the breakdown of his carefully managed mask.

Themes:

- Betrayal and self-deception

- The collapse of bourgeois domesticity

- The cost of being unseen

The Motel Room Scene – “You mean we’re going to sleep in the same room?”

Scene:

During the road trip, Humbert and Lolita arrive at a motel. She’s playful and teasing, but the moment she realizes they’ll share a room, her expression changes to discomfort. Later, while lying in bed, she begins to whisper about a game she played at summer camp — implying intimacy and manipulation, but through a child’s perspective.

Why It’s Classic:

- This is one of the most psychologically charged scenes in the film.

- Kubrick plays everything through tone, implication, and body language.

- Sue Lyon’s performance subtly shifts from cocky to vulnerable, revealing her confusion.

Themes:

- Power and control masked as affection

- Emotional grooming

- The psychological cost of ambiguity

The Beardsley School Scene – Parent-Teacher Conference

Scene:

Humbert attends a meeting with Miss Pratt, the school principal, who explains that Lolita is becoming disruptive and sexually precocious. Humbert tries to deflect, but the teachers’ concern is evident.

Why It’s Classic:

- The scene is played as a darkly comic satire of 1950s America’s prudish moral culture.

- The absurdity of the “concerned” educators is contrasted with the reality Humbert is hiding — that he’s the actual problem.

- Kubrick uses the scene to critique the blind spots of institutions.

Themes:

- Social denial and hypocrisy

- The absurdity of authority

- The failure to protect

The Final Confrontation – Humbert and the Adult Lolita

Scene:

Years after she disappears, Humbert finds Lolita again — now married, pregnant, and living in modest conditions. He offers her money to come away with him. She refuses. He breaks down, calling her “the only real love of his life.”

Why It’s Classic:

- Sue Lyon, now styled to look older and wearied, delivers a performance full of quiet pain and emotional distance.

- Humbert’s illusions collapse. He sees her not as a fantasy, but a human being.

- There’s no redemption, just realization.

Themes:

- Loss and regret

- Emotional consequence

- The final break between illusion and reality

Quilty in Disguise – Multiple Encounters

Scene(s):

Throughout the film, Quilty appears in strange disguises — as a detective, a hotel clerk, and other figures — always circling Humbert and Lolita. These moments are both comical and eerie.

Why It’s Classic:

- Peter Sellers’ improvisations add a surreal, destabilizing quality to the film.

- Quilty becomes a phantom double of Humbert — his rival, mirror, and eventual victim.

- These scenes inject the film with Kafkaesque unease, blurring reality.

Themes:

- Surveillance and paranoia

- Doubling and doppelgängers

- The absurdity of guilt

Awards and Recognition for Lolita

Academy Awards (Oscars) – 1963

- Nominated: Best Adapted Screenplay

- Vladimir Nabokov

Note: This was the film’s only Oscar nomination. Despite strong performances and direction, the controversial subject matter likely limited its recognition.

Golden Globe Awards – 1963

- Won: Most Promising Newcomer – Female

- Sue Lyon

- Nominated: Best Director – Motion Picture

- Stanley Kubrick

- Nominated: Best Motion Picture – Drama

- Nominated: Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama

- James Mason

The Golden Globes gave the film more recognition than the Academy, especially honoring Sue Lyon’s breakthrough performance.

BAFTA Awards – 1963

(British Academy of Film and Television Arts)

- Nominated: Best British Actor

- James Mason

- Nominated: Best Film from Any Source

- (Open category for international films)

Directors Guild of America (DGA)

- No nomination for Lolita.

Other Honors

- Included in the American Film Institute’s ballot for:

- AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies (though it didn’t make the final list)

- AFI’s 100 Years…100 Passions (nominee)

Legacy and Cultural Impact

While not heavily awarded at the time, Lolita has since grown in stature and is now considered a significant early work in Kubrick’s career, especially admired for its tone, direction, and psychological complexity.