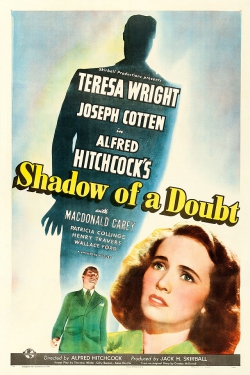

Shadow of a Doubt - 1943

back| Released by | Universal Pictures |

| Director | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Producer | Jack H. Skirball |

| Script | Story by Gordon McDonell - Screenplay by Thornton Wilder, Sally Benson, and Alma Reville (Hitchcock's wife and frequent collaborator) |

| Cinematography | Joseph A. Valentine |

| Music by | Dimitri Tiomkin |

| Running time | 108 minutes |

| Film budget | $600,000 |

| Box office sales | $1.5 million |

| Main cast | Teresa Wright - Joseph Cotten - Macdonald Carey - Patricia Collinge - Henry Travers |

Shadow of a Doubt

Evil Comes Home

Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) tells the story of young Charlie Newton, whose admiration for her visiting Uncle Charlie turns to fear as she suspects him of being a serial killer. Set in a peaceful small town, the film explores the dark undercurrents hidden beneath ordinary life.

With Joseph Cotten’s chilling performance and Teresa Wright’s emotional depth, the film slowly builds psychological tension without relying on overt violence.

Regarded by Hitchcock as his personal favorite, Shadow of a Doubt marked a turning point in his American career, blending domestic realism with suspense. Though modestly received in awards at the time, its reputation has grown, influencing generations of thrillers with its theme of evil lurking in the familiar. Today, it's hailed as one of Hitchcock’s most quietly devastating masterpieces.

Related

Shadow of a Doubt – 1943

Summary

Setting and Introduction

The film opens in a gritty urban setting—Philadelphia—where Charles Oakley (Joseph Cotten), a suave but mysterious man, evades two detectives who are closing in on him. He disappears and sends word to his sister's family in the small, idyllic town of Santa Rosa, California, that he's coming for a visit.

Meanwhile, his niece and namesake, Charlotte “Charlie” Newton (Teresa Wright), is bored with small-town life. She idolizes her uncle and believes his visit is fate—it will bring excitement and meaning to her uneventful days.

The Visit

Uncle Charlie arrives to great fanfare. He’s charming, well-dressed, and quickly becomes the center of attention. But cracks begin to form in the perfect surface. Young Charlie notices odd behavior: her uncle hides a newspaper clipping, seems overly controlling, and reacts with hostility when she brings up a certain issue.

The tension rises when two men arrive in town posing as survey takers. They’re actually detectives investigating a serial killer who preys on wealthy widows—known as the “Merry Widow Murderer.” Young Charlie begins to suspect that her beloved uncle may not be who he pretends to be.

The Shift

After some subtle sleuthing and a chilling dinner table monologue in which Uncle Charlie rants against rich, idle women, young Charlie grows convinced of his guilt. The uncle, realizing her suspicions, tries to gaslight her and even attempts to kill her—once by tampering with the stairs, then by locking her in a garage with a running car.

Terrified but determined, young Charlie confronts him. He admits nothing, but decides to leave town. On the train platform, in one final attempt to silence her, he tries to push her off a moving train. Instead, she turns the tables and he falls to his death.

Conclusion

At his funeral, the town remembers Uncle Charlie as a misunderstood, tragic figure. Young Charlie, carrying the weight of the truth, chooses to keep his secret. She whispers it only to her detective friend Jack Graham, hinting that she’ll live with the burden but move forward, wiser and more grounded.

Analysis

Themes

- Duality and the Nature of Evil: Hitchcock explores the idea that evil can hide behind charm and familiarity. Uncle Charlie is affable and magnetic, yet he’s a cold-blooded killer. Santa Rosa is peaceful on the surface, but corruption infiltrates it from within.

- Loss of Innocence: Young Charlie represents youthful idealism. Her journey from admiration to disillusionment mirrors a universal rite of passage: the recognition that people, even those we love, can harbor darkness.

- Family and Identity: The film examines how identity is tied to family. Young Charlie’s bond with her uncle is both symbolic and literal—they share a name, and initially, a deep connection. Breaking away from him is also a symbolic act of self-definition.

- Small Town vs. Big City: Hitchcock contrasts the supposed innocence of small-town life with the dangerous allure of the big city. But he ultimately subverts this idea by showing that evil can take root anywhere.

- The Mask of Civility: A recurring Hitchcockian motif—evil dressed in everyday clothing. Uncle Charlie wears suits, brings gifts, and quotes poetry. Yet he despises the very society he pretends to charm.

Character Dynamics

- Uncle Charlie: A prototype of the charming sociopath. He has no remorse and justifies his murders with a twisted worldview. Joseph Cotten’s performance is chilling in its restraint—smiling while implying menace.

- Young Charlie: She evolves from naive and dreamy to perceptive and morally strong. Teresa Wright portrays this transformation with sensitivity and strength. Her disillusionment is central to the film’s emotional core.

- The Newton Family: Represent the complacency of middle America. They are loving but oblivious. Their blind trust in Uncle Charlie heightens the film’s tension and illustrates Hitchcock’s warning: evil often hides in plain sight.

Visual and Stylistic Elements

- Cinematography: Hitchcock and cinematographer Joseph Valentine use deep shadows, strategic lighting, and expressionistic camera angles. Notably, Uncle Charlie is often shot from below, giving him a menacing stature, while young Charlie is filmed with more open, light-filled framing—until her innocence begins to fade.

- Symbolism:

- The train: Symbolizes the arrival of danger. Uncle Charlie’s train brings death into Santa Rosa.

- The ring: A damning clue—it has the initials of one of the murdered widows.

- Waltzing music: “The Merry Widow Waltz” haunts the film, both diegetically and thematically, linking Uncle Charlie to his crimes.

Legacy and Impact

- Hitchcock considered Shadow of a Doubt his favorite among his films.

- It marked a shift in his storytelling toward psychological complexity rather than just suspenseful plotting.

- The film has influenced countless later thrillers that explore the dark side of domestic life (Blue Velvet, The Stepfather, Stoker, etc.).

- It’s a masterclass in slow-burn suspense and emotional stakes, rather than cheap thrills.

Main Cast:

- Teresa Wright as Charlotte "Charlie" Newton

- Joseph Cotten as Charles Oakley (Uncle Charlie)

- Macdonald Carey as Jack Graham (Detective / Charlie's love interest)

- Patricia Collinge as Emma Newton (Charlie's mother / Uncle Charlie’s sister)

- Henry Travers as Joseph Newton (Charlie's father)

- Hume Cronyn as Herbie Hawkins (Newton family friend and amateur sleuth)

- Wallace Ford as Fred Saunders (Detective)

Supporting Cast:

- Edna May Wonacott as Ann Newton (Charlie's younger sister)

- Charles Bates as Roger Newton (Charlie's younger brother)

- Irving Bacon as Station Master

- Earle S. Dewey as Dr. Phillips

- Vaughan Glaser as Mr. Gifford (Bank manager)

- Janet Shaw as Louise Finch (Bank secretary)

- Estelle Jewell as Catherine (Charlie's friend)

- Frances Carson as Mrs. Potter

- Sarah Edwards as Mrs. Henderson (Woman on train)

- Clarence Muse as Pullman porter

- Herbert Evans as Pullman conductor

Classic Trailer Shadow of a Doubt

Direction Analysis – Alfred Hitchcock in Shadow of a Doubt

Alfred Hitchcock’s direction in Shadow of a Doubt is a study in psychological tension, moral duality, and subtle dread, delivered with precision, restraint, and an almost surgical understanding of human behavior. This is Hitchcock at his most nuanced, less concerned with spectacle and more interested in the quiet invasion of evil into everyday life.

Evil in the Ordinary

Hitchcock sets Shadow of a Doubt in the seemingly idyllic American town of Santa Rosa, California, a place of picket fences, home-cooked dinners, and nosy but good-natured neighbors. By introducing danger into such a serene setting, Hitchcock creates a chilling juxtaposition: the safest place on earth becomes the stage for moral decay.

- Direction choice: He refrains from Gothic lighting or exaggerated suspense cues early on. Instead, he allows dread to build organically as the audience begins to sense that Uncle Charlie may not be what he seems—long before anything is confirmed.

Visual Storytelling and Subjective Camera

Hitchcock uses the camera not merely to observe but to implicate. He masterfully aligns the audience with young Charlie’s point of view, allowing us to see through her eyes, sense her discomfort, and share her growing realization.

- Example: When young Charlie looks at the inscription on the mysterious ring, Hitchcock zooms in slowly and holds the moment. There is no musical sting or spoken word—just visual tension that speaks volumes.

- He often shoots Uncle Charlie from below, creating a looming, almost mythic presence, while young Charlie is shot from eye level or above, symbolizing her innocence and vulnerability.

The Use of Suspense

Hitchcock famously differentiated between surprise and suspense. In Shadow of a Doubt, he leans heavily into suspense. He lets the audience discover Uncle Charlie’s secret before the heroine fully does, creating a slow, unbearable tension.

- The suspense is not driven by chases or violence, but by conversation, glances, and silences. It is suspense built on the emotional stakes between family members—what happens when you suspect the person you love the most may be a murderer?

Thematic Control and Psychological Depth

Hitchcock’s direction underscores the film’s core themes: duality, corruption, and the loss of innocence. He visually and structurally mirrors the characters of Uncle Charlie and young Charlie—two sides of the same coin, one descending into darkness, the other fighting to stay in the light.

- Their mirrored names (both "Charlie") are symbolic, and Hitchcock makes that parallel clear through their framing and blocking. They often share the frame, positioned like opposing reflections—two paths, two moral directions.

Pacing and Narrative Rhythm

Hitchcock deliberately slows the narrative tempo in the first half. He allows the audience to settle into the cozy rhythm of small-town life, which makes the later unraveling all the more disturbing. The second half escalates subtly, with Hitchcock never tipping into melodrama—his direction is measured, internalized, and intimate.

- Even the attempted murders are understated—an untied stair, a locked garage. These aren’t cinematic set pieces; they are terrifying precisely because they feel plausible.

Use of Sound and Music

While Dimitri Tiomkin composed the film’s score, Hitchcock’s direction carefully controls its placement. The “Merry Widow Waltz” becomes a sinister motif, often tied to Uncle Charlie’s presence. Hitchcock uses silence just as effectively—long, uncomfortable pauses often speak louder than dialogue.

- In scenes of revelation or tension, Hitchcock pulls back sound entirely, making the audience lean in, heightening the discomfort.

The Hitchcock Cameo

In classic fashion, Hitchcock appears briefly—in this case, on the train to Santa Rosa, playing cards. His placement is casual and blink-or-miss, but thematically relevant: he holds a full hand of spades, symbolizing death and fate. It’s a small touch, but it exemplifies his attention to detail.

Direction of Actors

Hitchcock was often known for being emotionally detached from actors, but in Shadow of a Doubt, his direction elicits some of the most emotionally grounded performances of his career:

- Joseph Cotten is chilling because of his calmness; Hitchcock directed him to play Uncle Charlie as both seductive and sickened, a man who despises the world but wants his family’s love.

- Teresa Wright gives a layered performance as she shifts from adoration to horror. Hitchcock allows her to breathe in every scene, letting emotion build slowly and credibly.

Conclusion:

Hitchcock’s direction in Shadow of a Doubt is restrained yet masterful, focused on mood, psychology, and the fragility of trust. He doesn’t rely on tricks or gimmicks but instead builds dread through the slow corrosion of intimacy. It’s a portrait of evil not as a distant threat, but as something that walks into your home and sits at your dinner table.

This film marked a turning point in Hitchcock’s American career. It’s where he truly began to explore the darkness within the domestic, a theme he would revisit again and again—with more technical flair in later years, but rarely with such emotional precision and moral weight.

Teresa Wright as Charlotte “Charlie” Newton

A performance of subtlety, depth, and emotional awakening

In Shadow of a Doubt, Teresa Wright delivers what is arguably one of the most emotionally resonant performances in any Hitchcock film. Her portrayal of young Charlie is not only believable and layered—it anchors the film’s central themes of innocence shattered, moral reckoning, and personal transformation.

Embodying Innocence Without Naïveté

At the beginning of the film, Wright plays Charlie as a restless, intelligent, and idealistic teenager—a young woman who yearns for something greater than the stifling comfort of small-town life. She’s not childish, but she is clearly untested by the world. Wright communicates this restlessness through a light, quick delivery of lines, animated expressions, and a physical energy that borders on impatient—pacing rooms, darting between family members, leaning into others' words.

- Her eyes are wide with curiosity and admiration when she hears that Uncle Charlie is coming to visit—this isn’t just an uncle, but a figure of excitement and mystery who might rescue her from boredom.

- Wright infuses her character with an early sense of dreamy idealism, but she never plays Charlie as foolish. She is curious, thoughtful, and emotionally engaged from the very first scenes.

The Slow Unraveling – A Portrait in Internal Conflict

As suspicions about Uncle Charlie begin to form, Wright shifts her performance almost imperceptibly. Her body language closes off. Her voice grows quieter, more measured. There’s a brilliant stretch of the film in which young Charlie knows something is wrong—but not yet what—and Wright plays those moments with aching precision.

- She doesn’t rely on melodrama. Instead, Wright allows the horror to build in her eyes, in small hesitations, in the way she stops trusting her own instincts.

- One standout moment is when she confronts Uncle Charlie over the missing newspaper article. Her line delivery is tentative, laced with forced calm, but her posture is defensive. It’s a performance of emotional containment—young Charlie is scared, but she refuses to be weak.

Transformation Through Terror

Wright’s greatest triumph lies in her depiction of young Charlie’s loss of innocence. This is not a sudden event but a gradual erosion of trust, safety, and familial love. As the film progresses, Wright lets go of the breeziness of her earlier performance and replaces it with quiet determination.

- The shift is most notable in her eyes and voice. She stops looking up to others, especially Uncle Charlie. Her gaze becomes direct, and there’s steel in her words—even as fear mounts.

- The scene where she locks eyes with Uncle Charlie in the library, after confirming his guilt, is played with almost no words, yet Wright’s performance says everything: betrayal, heartbreak, moral fury.

The Heroism of Emotional Strength

Wright never portrays young Charlie as a conventional heroine. She isn’t strong because she physically overpowers anyone—she’s strong because she feels deeply and refuses to turn away from the truth. Hitchcock, who often relegated female characters to either icy blondes or screaming victims, gives Wright an unusually complex emotional arc—and she rises to meet it with intelligence, vulnerability, and resolve.

- Her final confrontation with Uncle Charlie is not triumphant, but weary. She doesn’t gloat in victory; she mourns what has been lost. Wright conveys this with hushed tones and a haunted stillness.

- At the funeral, her subtle smile is tinged with pain, not relief. The performance never overstates—it trusts the viewer to see the emotional cost of survival.

Chemistry and Contrast

Wright’s dynamic with Joseph Cotten is pivotal. Their performances are like a mirror slowly cracking. Cotten oozes charm with menace; Wright counters with warmth that turns to wariness. Their scenes together are electrified not by volume or violence, but by emotional tension and unspoken dread.

- Early scenes show an affectionate closeness—Wright leans into his presence with joy. Later scenes are built on distance and recoil, even when they share the same room. That shift is largely driven by Wright’s performance—her physical presence becomes a moral barometer for the audience.

Conclusion: A Fully Realized, Emotionally Grounded Performance

Teresa Wright’s performance in Shadow of a Doubt is one of profound emotional range, executed with elegance and psychological clarity. She charts a journey from innocence to wisdom without a single false note. Her young Charlie is not just a character within a thriller—she is the film’s moral soul, its conscience, and ultimately, its quiet hero.

Few actresses of the era could have balanced warmth, intelligence, fragility, and steel as seamlessly as Wright does here. In a film about shadows, her performance is the light by which we see the truth.

Key Quotes from Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

Uncle Charlie (Charles Oakley):

“The cities are full of women, middle-aged widows, husbands dead... husbands who have spent their lives making fortunes, working and working. Then they die and leave their money to their wives. Their silly wives. And what do the wives do? These useless women! You see them in the hotels, the best hotels, every day by the thousands. Drinking the money, eating the money, losing the money at bridge, playing all day and all night. Smelling of money. Proud of their jewelry but of nothing else. Horrible, faded, fat, greedy women.”

Why it matters:

This is the most revealing monologue in the film, delivered chillingly at the family dinner table. It's where Uncle Charlie momentarily drops his charming facade and expresses his misanthropic, misogynistic worldview—one that justifies his killings. The speech horrifies young Charlie and marks a turning point in her suspicions.

Young Charlie (Charlotte Newton):

“We're not just an uncle and a niece, it's something else. I know you. I know that you don't tell people a lot of things. I don't either. I have the feeling that inside you somewhere, there's something nobody knows about.”

Why it matters:

Early in the film, young Charlie expresses an eerie emotional kinship with her uncle. This quote foreshadows the dark revelations to come and highlights Hitchcock’s theme of mirrored identities—two Charlies, two paths.

Uncle Charlie:

“You live in a dream. You're a sleepwalker, blind. How do you know what the world is like? Do you know the world is a foul sty? Do you know, if you rip the fronts off houses, you'd find swine?”

Why it matters:

Uncle Charlie directly challenges young Charlie’s idealistic view of the world. This quote represents his nihilism and his belief that beneath all appearances lies rot and corruption. It’s a moment of confrontation between two opposing worldviews.

Young Charlie:

“Go away, or I'll kill you myself. See, that's the way I feel about you.”

Why it matters:

A rare moment of rage and resolve from young Charlie. After being gaslit and nearly killed, she asserts herself. It's the moment when she fully breaks from her uncle emotionally, morally, and symbolically.

Uncle Charlie (to Young Charlie):

“You think you know something, don't you? You think you're the clever little girl who knows something. There's so much you don't know... so much.”

Why it matters:

This line drips with menace and condescension, as Uncle Charlie tries to reassert control over young Charlie. It’s an intimate and threatening line that reinforces the psychological warfare between them.

Young Charlie (closing voiceover):

“There was so much he didn't know. So much. But I think he knew more than we ever dreamed. And the world is not what I thought it was.”

Why it matters:

The final line of the film, a somber reflection that encapsulates the loss of innocence and the heavy moral burden that young Charlie now carries. It's a quiet, devastating end to her character arc.

Herbie Hawkins (Hume Cronyn):

“The murderer can't fool me. He's a man like myself, only twisted. I understand him.”

Why it matters:

This is a comic line delivered by Herbie, the Newtons’ neighbor, in a conversation about murder mysteries. Ironically, his statement applies directly to Uncle Charlie, who is indeed just like any other man—just twisted. It serves as darkly humorous foreshadowing.

Classic Scenes from Shadow of a Doubt

The Dinner Table Monologue – “The World is a Foul Sty”

Scene Summary:

During a seemingly ordinary family dinner, Uncle Charlie launches into a startling rant about wealthy widows, describing them as “useless women” and “fat, greedy swine.” The room falls silent. Young Charlie, visibly disturbed, begins to realize that her beloved uncle may be hiding something sinister.

Why it’s classic:

- It’s the first time the mask slips. Hitchcock doesn’t rely on music or dramatic cuts—the tension is purely in the words and reactions.

- Joseph Cotten delivers the monologue with eerie calm, which makes it more chilling.

- Teresa Wright’s non-verbal performance (her slow shift in posture, downcast eyes, clenched hands) tells the audience everything about her dawning horror.

The Library Scene – The Ring Revelation

Scene Summary:

Young Charlie goes to the library to research the mysterious newspaper clipping Uncle Charlie tried to hide. There, she confirms that he is suspected in the “Merry Widow Murders.” She then examines the ring he gave her—and finds an inscription from one of the victims.

Why it’s classic:

- Hitchcock builds suspense through silence and facial expression rather than dialogue.

- The use of the ring as a visual clue is subtle yet unmistakable—it becomes the turning point in the story.

- The atmosphere in the library is quiet and serene, making the revelation feel more intimate and chilling.

The Staircase “Accident”

Scene Summary:

Young Charlie almost takes a deadly fall when the step on the staircase suddenly collapses. It's later clear that Uncle Charlie engineered the incident to look like an accident.

Why it’s classic:

- A great example of Hitchcock’s use of everyday spaces (a family home) to stage moments of danger.

- The scene is filmed from above and below, emphasizing height and potential fall.

- It’s a moment of physical danger that parallels the emotional threat now looming.

The Locked Garage – The Second Attempt

Scene Summary:

Later, Uncle Charlie locks young Charlie in the garage and starts the car, trying to asphyxiate her with exhaust fumes. She narrowly escapes.

Why it’s classic:

- Another murder attempt disguised as an accident—Hitchcock plays with the theme of hidden intent under domestic normalcy.

- The silence of the garage, the hiss of the engine, and the slow realization of what’s happening build unbearable tension.

- Wright’s performance again elevates the scene—her panic is real but never exaggerated.

The Train Platform Confrontation and Final Struggle

Scene Summary:

In the climax, Uncle Charlie boards a train to leave town, believing he’s escaping suspicion. But he makes one last attempt to kill young Charlie by pushing her off the moving train. Instead, she resists and he falls to his death.

Why it’s classic:

- A literal and symbolic climax—Uncle Charlie is destroyed by the very momentum he set in motion.

- The train, which brought evil into Santa Rosa, now takes it away, at the cost of his life.

- The scene is fast, physical, and emotionally charged—but Hitchcock still avoids overplaying it. The death is sudden and abrupt, just as real violence often is.

The Funeral and Voiceover Epilogue

Scene Summary:

The family mourns Uncle Charlie, unaware of the truth. A detective asks young Charlie if she’ll ever tell anyone what really happened. Her voiceover delivers the film’s final words: “The world is not what I thought it was.”

Why it’s classic:

- The emotional resolution of the film. Hitchcock avoids a traditional “gotcha” ending and instead gives us quiet sorrow and moral reflection.

- Wright’s delivery is calm, but her face is weighted by the trauma of what she’s endured.

- It’s a haunting, melancholic close—there’s no triumph, only knowledge and loss.

Conclusion:

Each of these classic scenes plays into Hitchcock’s larger vision: the idea that evil can nestle quietly within the familiar, and that the real horror lies not in the grotesque, but in the gradual betrayal of trust. With minimal action and maximum implication, Hitchcock uses these scenes to transform Shadow of a Doubt from a simple mystery into a profound psychological thriller.

Awards and Recognition

Academy Awards (Oscars)

- Nomination – Best Writing, Original Story

– Gordon McDonell

Note: This was the film’s only Oscar nomination, despite later recognition as one of Hitchcock's greatest works.

National Board of Review (1943)

- Included in the Top Ten Films of the Year

The National Board of Review recognized the film's high artistic quality, placing it alongside other important works of the era.

New York Times (1943)

- Selected as one of the Ten Best Films of the Year by critics

While not a formal award, this distinction reflected the film’s critical acclaim upon release.

American Film Institute (AFI) Recognitions

Though not awarded at the time of release, Shadow of a Doubt has since been honored in several AFI lists, highlighting its enduring legacy:

- AFI’s 100 Years... 100 Thrills (2001)

– Ranked #38 - AFI’s 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains (2003)

– Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) ranked #67 Villain - AFI’s 10 Top 10 – Mystery Film Category (2008)

– Ranked #9 mystery film of all time

Library of Congress – National Film Registry

- Selected in 1991 for preservation by the United States National Film Registry

Honored as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”